Winners and Losers: The Appeals Court and the Métis as “Indians”

Ottawa has a history of appealing Aboriginal victories in the courts.

Ottawa has a history of appealing Aboriginal victories in the courts.

So far, its fight over recognition of jurisdictional responsibility to Métis people has run up a multi-million dollar tab, and everyone watching the last Federal Appeals Court ruling expects lawyers will be dining out very nicely on the file again and again.

In April 2014, the Appeals Court ruled Ottawa must regard the Métis in the same light as “Indians” under the Constitution. It seems so obvious. It’s there in black and white in Section 35 (2) of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms which flatly states: Métis people, like Indians and Inuit, are Aboriginal. Meaning, when you read the word “aboriginal” in the Constitution, it covers Indians, Inuit and, yes, Métis people.

Justice Eleanor Dawson of the Appeals court used the definition of “Métis” people outlined in the Powley decision:

…the term refers to a distinctive group of people who developed separate and distinct identities. The three broad factors that are the indicia of Métis identity for the purpose of claiming Métis rights under section 35 were found to be: self-identification, ancestral connection and community acceptance.

But here’s the tricky part. That, in and of itself, does not guarantee Métis the same rights that many believe Indians enjoy under the Constitution. What’s more, ten million people of mixed Indian and European heritage will not automatically be regarded as Métis. (Which makes me wonder: if you are Indian-and-Asian or Indian-and-African, why are you NOT regarded as Métis? And why is it that such a great number of Indian Status holders who don’t actually have two native parents find themselves legally regarded as First Nations and not Métis?)

The fear among non-natives is that everyone in Canada is going to be on the hook for millions in costs for the education, healthcare and housing of Métis people. Those same non-natives also fear they’ll have to move because they’re living on land previously ceded by treaty to the original Aboriginal title-holders. That’s not what the ruling means. In its simplest form, what the ruling means is that if there’s a dispute about hunting and fishing rights, or a demand for daycare services, Ottawa can’t palm it off on a province or territory or municipality. Put in simpler terms still: Ottawa’s being told to suck it up and play by its own rules.

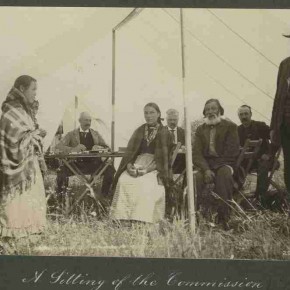

All along, the Métis argument has been that, constitutionally, Ottawa has had a fiduciary relationship with Métis people because it has all along regarded the Métis as Aboriginal. It did so decades ago when it wooed some Métis with the “Scrip” scam — promising land entitlement if they would only vacate any claims against the government. It did so over half a century ago when it created a ‘no alcohol’ law and applied it to Indians “and others like them.” It literally spelled it out in the 1982 British North America Act. In short, Ottawa wrote the very rules it has argued do not really apply here.

Some historical Métis communities — including that of Rainy River in Ontario, St. Paul des Métis in Alberta, and the Red River Métis of Manitoba — have had documented agreements with Canada. For land and services. With spotty delivery records to be sure, but agreements, unfulfilled or not. They are proof. So Ottawa is being told to take its medicine.

But the same Appeals court ruling found — strangely, I think — that those deemed “non-Status Indians” aren’t necessarily “Indians” constitutionally. These are people who lost Status when they married out of the community. Or who walked away from their communities to avoid racism from outside by “passing” as something else. Or the children of relationships in which one partner is not recognized as a band member. Or people who move away for a job, relationship, safety or housing and don’t go home again. Keep in mind, some bands have very stiff regulations about membership dealing with blood percentages or family trees or unbroken residency. Feuds on the rez can leave you on the outside of all decision making and those rules never get changed.

The upshot, as far as I can interpret it, is the Appeals court was signaling that Ottawa has a constitutional obligation to a “group” but not the individuals who make up the group. And if that is the case, it may be time to start looking around to see if you live in a “community” of Métis people — or if you are a Métis resident of a varied community. Because the things that make you Métis — having the genetic makeup, self-identifying that way and speaking michif — aren’t enough when the battle moves to a fight for education or housing. Ottawa has an obligation to communities of people. And in the legal system, that usually calls for historically defined communities.

Which means all those people who drifted or ran away to make a better life, or to gain the right to vote, or get a chunk of land to call their own or for any other coercive reason, are only likely to gain moral satisfaction from this ruling.

Not a bad start I’d say.