Most First Nations See Right Through Canada’s Transparency Act

NOTE: An edited, abridged version of this piece first appeared on Ricochet, the Canadian multi-platform news outlet, back in early December 2014.

. . . . . .

From its name alone, you immediately sense that you’re not getting the whole story—the First Nations Financial Transparency Act.

Passed in March 2013, the law is only truly coming into effect now. Ostensibly a way to finally peel the curtain back on what one can only assume is the near-universal financial opacity of First Nations—like, are you telling me Ottawa would go the route of an across-the-board law if there weren’t widespread problems? I mean, who’s against transparency, am I right?—the FNFTA (pronounced ‘effin-F-T-A’) requires them “to make public the annual audited consolidated financial statements they must already prepare, as well as a schedule of Chiefs’ and Councillors’ salaries and expenses.”

That’s how Bernard Valcourt, the non-Indian Indian Affairs Minister, described the jist of the Act in a ‘letter to the editor‘ proudly posted to his Department’s website. (It ‘modernized’ its name some years ago to become Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada or AANDC, but I still call it Indian Affairs.)

Valcourt justified it as “an important milestone for those First Nation community members who have been calling for greater transparency and accountability from their Chiefs and Band Councils.” (Something not mentioned in that particular letter but noted elsewhere is that such reports must include revenues connected to First Nation-owned corporations, partnerships and joint ventures, making it even more controversial for some communities.)

The effective deadline for sharing that financial information recently came and went, and not everyone has complied with the Act by publicly posting their numbers on-line. (You can see that list of Very Bad Indians here.) And for that non-compliance, those First Nations could face consequences like a court order and/or the withholding of funding “for non-essential programs, services and activities until the requirements are met,” according to an AANDC letter obtained by the CBC. What’s more, the CBC also reported, the government could elect to “halt new or additional funding or end funding agreements entirely” as soon as December 12 unless uncooperative First Nations become cooperative. Clearly, AANDC is not messing around.

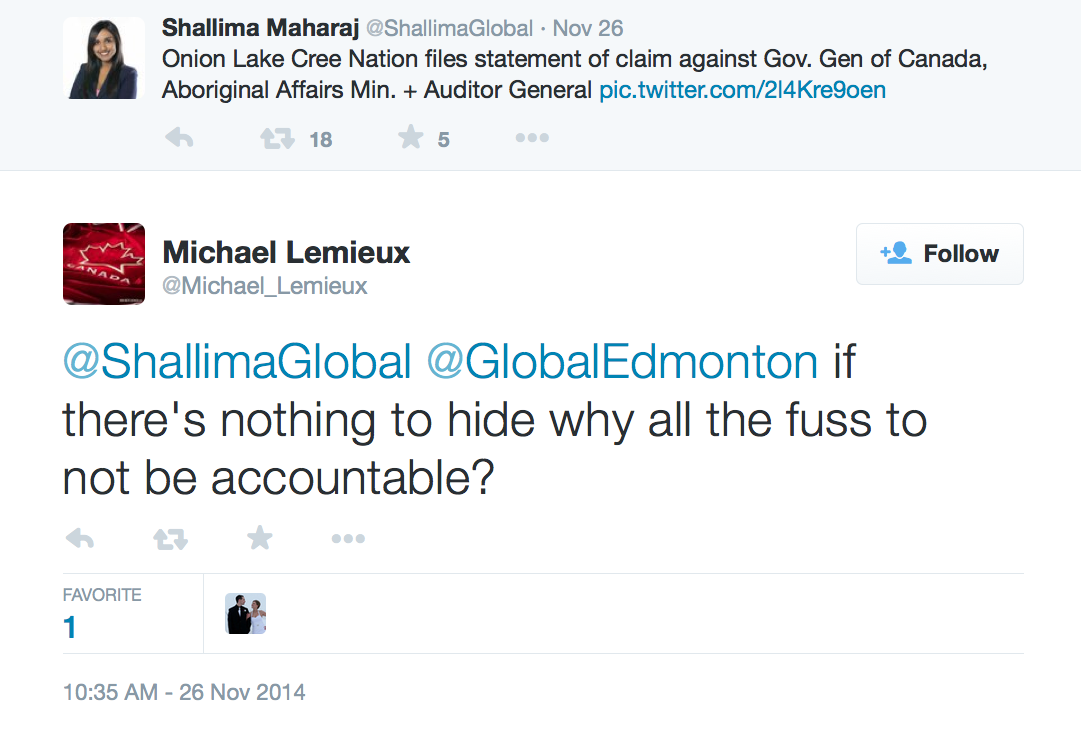

In response to such tactics, at least one First Nation has filed suit against the federal government, while others say they’re ready for a legal fight and invite the feds to come after them. With such exacting demands now placed on First Nations, one would expect that The Department itself is an exemplar of accountability and transparency. One would be wrong.

Take, for example, the results of the “Annual Report on the State of Performance Measurement in Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada for 2011-12 and 2012-13.” As the name likely tells you, it’s a byzantine Treasury Board effort to, among other things, measure the quality of The Department’s performance and relevance. It’s brutally boring reading that’ll make your eyes bleed, but here are some nuggets. For the criterion of “Clear Accountability,” Aboriginal Affairs has slipped from ‘Acceptable’ to ‘Opportunity for Improvement.’ (Like when your kid’s ‘not achieving their full potential’ in school. Time to buck up, Bernie!) On the matter of ‘Quality and Credible Performance Information,’ AANDC’s moved from a lot of ‘Attention Required’ to just ‘Attention Required.’ Good to know they’ve paid at least a little more attention to things.

As the National Post’s John Ivison put it:

“The department was measured on 10 criteria and got the equivalent of 2 Bs, 6 Cs and 2 Ds. The only reason Aboriginal Affairs is not at rock bottom and still digging is that the previous report two years ago was even more abysmal.”

Remember, these are the people hectoring First Nations to get their shit together. Rich stuff from a group that is unable to earn a ‘Strong’ rating in any of the 10 relevance/performance categories. Now, before you go jumping to any conclusions here, you should know that, according to AANDC, “these reports are not audits nor are they ‘report cards’ on the department’s activities.” Ivison also noted in his piece that the Minister said things have gotten better since the report was done, although the recent Auditor General’s report on Nutrition North leaves one sceptical. As you read some of these choicer quotes from the Annual Report (remember, it’s not a report card, it’s an assessment of performance—HUGE difference), I wouldn’t blame you for thinking that getting better in this case is mostly getting off the floor.

- “While the Department collects a vast amount of data, much of the data remains unanalysed.”

- “Cost-effectiveness remains an area with few indicators dedicated to it, making it difficult for the Department to report on questions of efficiency and economy.”

- “A lack of communication… duplication of information and missed opportunities to learn from past mistakes.”

- “…the Department continues to struggle with the quality and credibility of its information…”

Usually a record that woeful inspires bureaucrats to find a distraction, and fast. Wonder who they got us to focus on instead? Oh, right, those Indians that The Indian Department is theoretically supposed to serve. On that score, they’ve performed wonderfully.

But that’s just The Department. Pull back to focus on the federal government as a whole, and we see there’s plenty of fogginess to go around—financially or otherwise. In another CBC report from 2013, Canada’s Information Commissioner was quoted as saying the current federal government is “not the most transparent,” that “we are at a record low in terms of timeliness… [and] the percentage of information being disclosed is also low” when it comes to responses to requests for Access to Information. (FYI, guess which department was among those who got an ‘F’ grade from the Commissioner? Yep: Indian Affairs.)

Still, perhaps I am a tad naïve to think that double-standards or hypocrisy matter very much in this political arena. And lest I be misunderstood here, know that I am among the least surprised of anyone when I hear of Indigenous people experiencing their share of such offenses. But are they the norm, or simply outliers? If the latter, then why invest such vehemence into this effort when so much more pressing issues and challenges facing Indigenous peoples are in dire need of attention?

Recall that, in 2010, the average salary amongst Chiefs was, according to the Assembly of First Nations, some $36,000 a year. Another analysis by Macleans back in September of just over 325 Chiefs’ info found a median salary of $62,426. Such figures would make for some pretty boring headlines: most outlets obviously go straight for the outlandish and outrageous because it grabs attention and stirs emotion. But, as Hayden King has pointed out in his cogent critique of the FNFTA, few in the media decided to “cover the hundreds of chiefs and/or councils that make $10,000 a year… [or] examine the extreme AANDC underfunding this new data reveals.” Knowing that the average mainstream reader is unfamiliar with this history and context, the politicos who pushed this strategy rely on that ignorance, in the hopes that most will be left with the impression that what is relatively rare and complicated is instead endemic and basic to First Nations.

Admittedly, I’ve only scratched the surface here. For more reflection on the problematic nature of this Act—even when judged on its own terms—I recommend you read the aforementioned piece by Hayden King, this recent essay by Pamela Palmater, and this lengthy critique of the Act delivered in the Senate by Senator Lillian Dyck. Taken as a whole, you’ll hopefully come away with a more nuanced view of this effort at so-called ‘transparency,’ an approach that right now seems to obscure as much as it reveals.

That’s the funny thing about transparency: often, when a politician tries to paint a picture of someone else’s shortcomings, that’s usually the moment when people see right through them. And in this case, the closer we look at the cynical manipulations that lay behind this semi-subtle smear job against an entire population, the more things start to appear utterly transparent.