An Ink-stained Response to ‘Disrobing the Aboriginal Industry’ (Pt. 2)

Picking up where Part One left off, this piece is the second in a two-part response to Frances Widdowson and Albert Howard’s Disrobing the Aboriginal Industry: The Deception Behind Indigenous Cultural Preservation. It originally appeared in somewhat different forms in guest editorial/commentaries for Kanata (Vol. 1) and the Winter 2009 (#203) issue of Canadian Literature: A Quarterly of Criticism and Review.

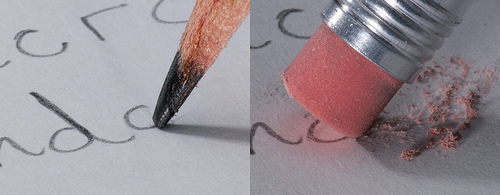

With pencil and eraser firmly in hand, and backed by a mainstream university press, Widdowson and Howard have composed an all-too familiar song of assimilation in the name of “progress.”

Their one-dimensional politics, historicism and century-old arguments are known well by First Nations peoples, communities and nations, who continue to endure ongoing attacks on their personal, communal and national sovereignties. The notion that this type of myopia is precisely why the current climate exists and perpetuates itself — not to mention that the authors’ “dream” of more of the same — is found nowhere in their pencil marks.

The truth that, like their western counterparts, expansive Indigenous intellectual systems, languages, governments and cultures change, grow and adjust, and just might have made valuable contributions to “human survival,” “development” and the “interconnected and complex global system” [5] is lost on them.

And if these ideas stopped here, I might too. These authors’ view of Indigenous peoples, their relationship with Canada, and the ways they should “develop” are endorsed by scholars such as Tom Flanagan (author of First Nations? Second Thoughts), political think-tanks such as the Frontier Centre for Public Policy, and by national Globe and Mail columnist Margaret Wente. Their vision is also strikingly mirrored by many practices and policies of the federal governing Conservatives and Prime Minister Stephen Harper, and, sometimes, their predecessors, too.

For example, take the now eleven-year-old cap of 2% on social, education, and economic funding for Native governments and their reserves, the refusal on September 13, 2007 to ratify the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and the reneging on the 2005 Kelowna Accord — an agreement between the federal government and all major Native organizations that was supposed to broker a wave of Indigenous self-determination, economic self-sufficiency and a “new” relationship with Canada — with virtually nothing put in its place.

Or, consider the moves in February 2009 by Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) to radically change post-secondary funding for First Nations students. Essentially, if followed, what has been historically claimed and affirmed as a treaty right by both Canada and First Nations would become a loan-based, provincially-run program. INAC’s “official” explanation: Native students can learn “fiscal responsibility” by taking out loans, “value” education more, and colleges and universities “are not” in “the original wording” of the treaties. The change in policy directives has expectedly been met with tremendous backlash.

There are other examples in other arenas. Go to any major department or new-age store. There you’ll find air-fresheners, souvenirs, and toys dressed up in colourfully painted, plastic and chicken-feathered headdresses, dream catchers, and smudge kits, with complete instructions on how “real” Indians use them.

There are other examples in other arenas. Go to any major department or new-age store. There you’ll find air-fresheners, souvenirs, and toys dressed up in colourfully painted, plastic and chicken-feathered headdresses, dream catchers, and smudge kits, with complete instructions on how “real” Indians use them.

Like static, archaic and empty relics, these items are easily explained, objectified and (most importantly) cheap. Erased are the historical, intellectual, and political significance of these items — treated as if legal, governmental and social contexts and ownerships can be extracted, removed or fixed in a tragic, disappearing past. Put in their place are ridiculous notions of authenticity — as if Native expressions and ideas haven’t changed in centuries.

Want others? Try the reality that there are no federally-recognized Indigenous language rights in Canada, while French and English enjoy protection, support, and money in all of their “official status” glory. Consider the fact that when Indigenous peoples defend their claims to territories and land they are labeled in the media and the public as illegal “squatters” interested in “anarchy” and “violence” (see: Oka, Caledonia, and protests against the Vancouver-Whistler 2010 Olympic construction projects). Think about how most ordinary Canadians don’t know that they are standing on treaty land right now, or that all of us benefit from treaties, or that each of us have ongoing responsibilities to uphold obligations as parts of these agreements.

I state all of this to show that Widdowson and Howard, while egregious in their claims, are not alone. While many have (rightfully) focused their efforts on engaging and upending their simplism, there is simply much more work that needs to be done. One-sided stories, erasure, and a landscape free of Native claims of sovereignty, land, and historical contributions still make up the bulk of North American culture. It’s the norm.

When people speak up and insist on Canada’s messy past being raised, discussed, and recognized, they are labeled ‘separatists,’ ‘angry’ and accused of perpetuating ‘falsehoods’ and ‘delusions’ — often to avoid responsibly and ethically engaging with their ideas. Then attempts are made to clean up the page, as Native peoples and their allies are ironically asked: “Why can’t you just be happy that Canada allows you to live, speak, and be free?”

Some change is happening. For all of the myopia and self-imposed ignorance embedded in these discourses, there is also responsible, ethical, and well-researched scholarship — most of which is provocative, rich, and multi-layered in its complex and diverse treatment of Indigenous peoples, communities, issues. Work produced by Native scholars in Canada such as Cheryl Suzack, Daniel Heath Justice, Deanna Reder, Kristina Fagan, John Borrows, Emma Laroque, Olive Dickason, Neal McLeod, Bonita Lawrence, Glen Coulthard, Chris Anderson, Jo-Ann Episkenew, Paul DePasquale, Linc Kesler, David Newhouse and Leanne Simpson (just to name a few) and non-Natives such as J. Edward Chamberlain, Peter Kulchyski, Arthur Ray, Daniel Francis, Sam McKegney, Margery Fee, Gordon Johnston, Keavy Martin, Daniel Morley Johnson and Renate Eigenbrod are models we should aspire to as responsible scholars and ethical researchers. Their work proves that all Canadians can partake in, learn from and engage with Indigenous histories, practices and intellectualism to make the spaces we share meaningful, respectful and beneficial for all. Change is slow, but it’s happening.

With all ideas, practices, and policies — ones we agree with and ones we don’t — Native Studies scholars must thoroughly interrogate and question our underlying claims, use reputable evidence to support our own, and always encourage honest and informed dialogues and debates among thinkers of diverse political and ideological opinions. Of course, this will result in spirited discussion, for these issues are about our collective futures and relationships as Native peoples, Canadians, immigrants — and sometimes all three.

We must therefore adopt, both personally and in our scholarship, a principle of respectful inter-responsibility embodied in the notion that we are ultimately neighbours, colleagues, and partners in this shared space called Turtle Island, or North America. We must also remind ourselves, and others, that Native nations and Canada, both historically and today, are more interrelated, interconnected, and reliant on one another than people tend to remember, recall, and conceptualize. “We are a métis civilization,” as John Ralston Saul writes in A Fair Country: Telling Truths about Canada, a people influenced by over five centuries of contact, influence, and growth with one another, and “[t]his influencing, this shaping is deep within us.”

And there’s something else we can do. Use our pens.

Rather, we can perceive the world and, in the ink of that knowledge, express our thoughts. We can speak of the beautiful ugliness in the history of this land. Insist on the permanency of Indigenous homes here. Reflect upon all of the nations and treaties that make up these spaces. Theorize Indigenous, settler, and Canadian intellectual histories, while recognizing that each have specific, rich, and important epistemologies, contributions, and histories that can dialogue. Sing about our interactive experiences, and ultimately learn from one another. Share stories, reflect, and listen— always listen.

And we can — perhaps most of all — make, accept, and cherish the messy blots, strokes, and smudges of our experiences on this earth, on these streets, in this life. Insist on this — even if it seems difficult, strenuous, and stressful — because this changes the world. Years of resistance and courage in the face of erasure, for example, is what made the 2008 Indian Residential School Apology happen. These tenets of Indigenous life are, in fact, why all of us are still here.

No matter how many professors, politicians, and citizens say that Aboriginal peoples, communities, nations are simple, static, and “dying,” as long as we do these things, Indigenous futures — and in turn our collective diversity, interests in equality, and inter-relationships with one another — will be ensured. I guarantee it.

FOOTNOTES

5. For more provocative ideas and opinions on Indigenous peoples perspectives on, and potential contributions to, globalization and world economic development, see Jerry Mander and Victoria Tauli-Corpuz’s edited collection of essays and opinions by twenty-seven scholars and activists from across the world, Paradigm Wars: Indigenous Peoples’ Resistance to Globalization.

[Top image via photobunny]

Hey I was searching for reliable information on inks for superwide printers. Your site was listed on Yahoo in this category, you have an informative site.