Sihkos’ Story: Residential school remembrances of a little brown ‘white’ girl

Jane Glennon (Woodland Cree), B.A., B.S.W., M.S.W., is a retired social worker, counsellor and teacher who currently lives in Prince Albert, SK. A member of the Peter Ballantyne Cree Nation, her published work includes “Traditional Parenting,” a chapter in the book, As We See… Aboriginal Pedagogy (University of Saskatchewan Extension Press, 1998).

Jane Glennon (Woodland Cree), B.A., B.S.W., M.S.W., is a retired social worker, counsellor and teacher who currently lives in Prince Albert, SK. A member of the Peter Ballantyne Cree Nation, her published work includes “Traditional Parenting,” a chapter in the book, As We See… Aboriginal Pedagogy (University of Saskatchewan Extension Press, 1998).

= = =

“The only way to save our dreams

is by being generous with ourselves.”

—Paulo Coelho

= = =

It has taken me a long time — literally decades — to try and tell my story, a story that I’ve never disclosed in its entirety to anyone, not even family. Accompanying me on my first steps down this path are the words of Paulo Coelho, the brilliant Brazilian writer whose works have sold over 100 million copies in sixty-nine languages. Coelho is among the authors I most admire and his writings truly inspire and motivate me, and after reaching out to him for counsel on the writing of my biography, Mr. Coelho shared with me the words you see above. It is in the spirit of his words that I now share mine.

* * *

I consider myself a product of the residential school era, but I do not consider myself a victim.

What I am is a survivor, and I can honestly state that, prior to being taken away to residential school, life consisted of positive childhood events and memories. I felt secure, safe, nurtured, and protected by my family. Much of those feelings changed in the schools I attended.

If you’ve heard or know little about these schools — launched in the 1870s, officially ended in 1986, when the last institution closed its doors — there is by now plenty of research and books written about the subject. One of the best is John S. Milloy’s A National Crime, in which he painstakingly traces the history and reality of the residential school era. Intent on ‘civilizing’ Aboriginal children by transforming little pagans into brown-skinned white members of society, the federal government enlisted the help of the Presbyterian, Anglican, United and Roman Catholic Churches.

Today, it is clearly evident that Canada has failed in its objective of absorbing First Nations people into mainstream society. But what it has done is seed dysfunction and despair among the thousands of Aboriginal people who’ve passed through the residential school system.

* * *

I was born in the late fall of 1940, in a little pine house my father built on a piece of land somewhere between the two northern Saskatchewan reserves of Pelican Narrows and Deschambault Lake (see map: click to enlarge). It was there that my family — Cree speakers all — first resided every fall, and it was there one early November some 72 years ago that a fair-sized baby girl with thick, unusually long black hair came into this world. Assisting in the delivery was my mother’s stepmother, a woman I would never again meet or remember. I was the fifth out of ten children.

Along with my hair, another trait setting me apart from the rest of my family was my medium complexion. As my siblings tell it, that dark hair, lighter skin combination inspired my nickname — sihkos, or ‘weasel’ in Cree, an animal known for its white fur and jet black tail. By the following springtime, my family moved to Deschambault Lake where, with the exception of winters, we lived for much of the next two years.

Along with my hair, another trait setting me apart from the rest of my family was my medium complexion. As my siblings tell it, that dark hair, lighter skin combination inspired my nickname — sihkos, or ‘weasel’ in Cree, an animal known for its white fur and jet black tail. By the following springtime, my family moved to Deschambault Lake where, with the exception of winters, we lived for much of the next two years.

My older sister Rose told me that I started to talk and walk from a very early age. I was also thought of as a replacement for another infant baby sister who had passed away. From as far back as I can remember, I felt very much loved by both parents: though I received special treatment, I never felt any jealousy from my siblings when extra attention was paid to me.

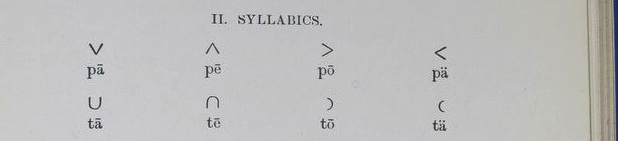

My parents noticed early on that I quickly understood what they taught me, and how I soaked up everything that I needed to know. Our parish priest used to teach the children Cree syllabics and he marveled at how fast I could learn. He tried to convince my parents that I was gifted and should go to school when the chance came along.

Some of my family’s memories of my first year include this anecdote from my sister Rose. One day, she and my mother were out walking along the shore checking traps. Meanwhile, my mother had me in tow on her back inside a wooden tihkinâkan, or cradleboard. Beautifully decorated, it had been made especially for me by my mother’s stepmother; Rose said it was worthy of being put on display in a museum. But on that particular day my mother had neglected to properly tie the cradleboard’s strings together. Consequently, I slipped out, and was very nearly dropped into the water next to the traps! Alas, that tihkinâkan would one day be stolen from our cabin while my family was away.

Personally, my most vivid childhood memory consists of the summer canoe trips my family took part in almost every year, typically in June, just prior to the beginning of the commercial fishing season. The canoe was filled up with my parents, eleven siblings plus as many as five dogs. With stops at other reserves as our destinations, travel used to take a week between each location. The best part of these excursions for me were the stopovers, whereupon the family enjoyed traditional foods such as moose meat, all kinds of berries, ducks, fish and other wild game. My father and brothers were good hunters and fishermen.

By the fall of 1943, my family had once again re-located, this time to Southend, a small Indian reserve based at the southern tip of Reindeer Lake in Saskatchewan. In winters, though, the family migrated to Jack Pine, a small settlement situated some distance from the reserve. I recall some happy times at Jack Pine, when relatives from other families would also winter there. My cousins and I used to play on the ice, making snow houses. Other times, we’d slide on a hill with pieces of cardboard boxes. One time, I had the bright and holy idea to enact the appearance of the Virgin Mary to three poor children in Portugal. My cousins made a makeshift grotto and each of us had a role to play. The parish priest used to tell us these type of stories; I must have been greatly impressed by this particular one. The Catholic religious indoctrination was certainly being ingrained even at this young age.

Another early memory dates back to our time at Jack Pine. At about age six, I developed an infection in both ears. With no medical help nearby, my father instructed my mother to sew two small canvas bags. He then proceeded to fill them with sand he had heated up on our wood stove. Covering the bags with towels, he held them on both of my ears, upon which my pain soon subsided and I fell into a sound sleep.

My parents knew a thing or two about medicinal matters, and there is a whole history of Aboriginal peoples using herbs and plants for such purposes. Like many at the time, my parents were familiar with muskrat root or wîhkes, a plant which apparently got its name from the way that this animal liked to chew on its white fleshy roots. Crushed wîhkes could both treat toothaches (when packed into a cavity) and sore throats (when used as a tea). Spruce tree gum was also useful: my mother would melt it in a frying pan with lard, making a creamy substance good for healing cuts and sores. A certain part of the bark of poplar trees was added to boiling water, with the resulting liquid given to mothers after birth to stop bleeding. I used to love gathering wild mint because I enjoyed the fragrance and the family loved its tea; it was also a good cough remedy, according to my grandmother. I remember gathering up moss from the muskeg and then hanging it to dry on a tree, after which I’d clean the moss for later use at home: inserted between two flannel cloths, the moss served as a diaper, a technique I was told would prevent rashes.

My parents knew a thing or two about medicinal matters, and there is a whole history of Aboriginal peoples using herbs and plants for such purposes. Like many at the time, my parents were familiar with muskrat root or wîhkes, a plant which apparently got its name from the way that this animal liked to chew on its white fleshy roots. Crushed wîhkes could both treat toothaches (when packed into a cavity) and sore throats (when used as a tea). Spruce tree gum was also useful: my mother would melt it in a frying pan with lard, making a creamy substance good for healing cuts and sores. A certain part of the bark of poplar trees was added to boiling water, with the resulting liquid given to mothers after birth to stop bleeding. I used to love gathering wild mint because I enjoyed the fragrance and the family loved its tea; it was also a good cough remedy, according to my grandmother. I remember gathering up moss from the muskeg and then hanging it to dry on a tree, after which I’d clean the moss for later use at home: inserted between two flannel cloths, the moss served as a diaper, a technique I was told would prevent rashes.

Poverty was an issue influencing my young mind at the time but I never expressed any dissatisfaction about my family’s living conditions. I recall how, as a young girl, I’d use a piece of fire wood as my doll because my parents could not afford to buy us toys. My friends and I would use empty food cans and discarded pieces of cloth to set up a store emulating the Hudson’s Bay Company, which operated the only retail outlet on the reserve. I used to have grand scale ideas about building my own house and had figured out all the details about how the home was going to look inside.

* * *

By the late 1940s, I would be of age to attend residential school. With no formal education available at Southend, the only option was for me to join the many other children already attending an institution located far away from home. My parents were Anglicans, and I remember vividly the priest at the reserve telling them, “The school does not take Protestants.” This meant my parents had to agree to get me baptized into Catholicism before I could be accepted into the residential school.

I remember not wanting to leave home. My parents were also reluctant to let me go because I was to be away for ten months of the year. The priest, however, reminded my parents of my potential and how quickly I learned. Meanwhile, the Indian Agent — a representative of the Department of Indian Affairs who dictated the lives of First Nations people through the Indian Act — emphasized the fact that Indian parents were required to send their children to these schools.

My first unhappy trip to a residential school took place one sad day in September 1949. It was a devastating time in my young life, and I have often wondered whether it was worth it. To this day, the sound of an airplane still triggers memories of the first time I had to leave home for school. It’s a sound that would repeat many times in my young life, as the plane came back to gather the children up for another ten months of loneliness and heartbreak.

My parents had insisted that I be accompanied at school by my older sister; her role was to take care of me there. Through the Indian Agent, my mother and father also requested that the school not cut my long black hair, which had always been done up neatly in pigtails.

I shed a lot of tears that first day of my first year of residential school. Even now, my eyes well up every time I remember it. To be separated from my family was beyond heartbreaking: I was so very lonesome and cried every night. My older sister tells me that she used to try to comfort me but would only end up crying with me.

Like so many Indigenous children before and after me, my life was about to change dramatically. Forced to embark upon a journey into a foreign environment and culture, I was now on my way into a totally different way of life. Little did I know at the time that this flight would be just the first of many, as I would spend much of the next ten years of my childhood in three separate residential schools across two Prairie provinces. In my next instalment, I will write of the first of these experiences.

This is a great article about a subject that’s affected so many. It’s even more compelling that it’s written by a residential school survivor. I wish my late mother had written her experiences as well.

As Jane’s son —Jane okosisa, if I remember my Cree correctly — I am very proud to work with her on sharing her story with the world; in her own way, she too is

“idle no more”: as a writer, that is, for she has always advocated for her

family and her people. I too very much look forward to further installments

I think there’s an error. Last school closed in 1996