Residency and identity: Bringing the Senate problem “home”

For the pod of senators facing pressure to prove their residential identity, the squeeze is on. Pressure to prove where they live, i.e., where they “reside,” according to the forms some senators have used to file expense claims.

For the pod of senators facing pressure to prove their residential identity, the squeeze is on. Pressure to prove where they live, i.e., where they “reside,” according to the forms some senators have used to file expense claims.

And while claiming a $22,000 a year allowance for a ‘second’ residence when you no longer live outside Ottawa plays like a wink and a finger alongside one’s nose, it’s not the thread pulling of the loophole that struck me as the big problem, it’s the notion of identity-by-residency. I say that because Senators are considered representatives of a province based on their ownership of property in that province.

(The same set-up also applies to Prime Ministers not originally from Canada but who became Canadian or hyphenated Canadian, e.g., Sir John A. Macdonald, Alexander Mackenzie, John Turner. But I digress.)

Put it this way: If you once lived in P.E.I., are you still an Islander if you now only visit there? If you didn’t come from there but have lived there for the last decade, does that make you an Islander?

Indigenous peoples face their own versions of these questions. Questions like: if you come from a reserve but now live far away in the city in order to be closer to your job, school and/or partner, is the reserve still “home?” Should you be classified as a band member if you don’t live or play with the band? Should you have to reside in, and contribute to the welfare of, the community in order to be ethically counted as a full-fledged member of the community?

The two scenarios aren’t precise equivalents because housing shortages and next-to-jobless economies make residence on most reserves a non-starter for many band members. So although you aren’t able to live on the reserve, you’re still with the band: your band affiliation travels with you. You’re Maliseet or Algonquin or Blackfoot wherever you live, no matter how long you’re gone. Might the same logic not hold true for our aforementioned Islanders?

What happens to your identity if you don’t have a home territory with distinct boundaries? That’s the situation confronted by most Métis people. Yes, your Métis identity travels with you wherever you go, but if you’re Métis from outside the Canadian historically-recognized Red River area of Manitoba — a myopic view according to some historians — where, then, is “home?” And effectively absent such a territory, what are we to make of the Federal Court’s recent decision that Métis people should be constitutionally regarded as “Indian” when it comes to what rights that decision confers?

To many non-native people, the court’s decision meant potentially worrisome payouts. But payouts linked to what? Establishing entitlement is generally tied to territory and to membership in a recognized community. Yes, some Métis were accorded territory over a century ago on the basis of “scrip,” an ill-intentioned extinguishment effort based on a land-for-identity swap. But how do you establish what to pay out to Métis claimants of no specific territory (if it is indeed money that’s being sought)? And though the federal government once sought to be the arbiter of “Métis-ness,” we have yet to resolve the question of who is, and who is not, Métis — or by whom. You can expect that discussion to come to a boil as we move closer to Ottawa’s appeal of the Federal Court ruling.

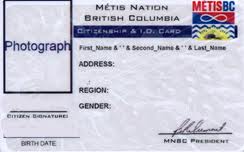

The concern is that, if there’s a purely financial benefit to somehow be had just from being called “Métis,” everyone will be filing for a Status card to get a piece of that pie. The Métis of BC are taking a shot at minimizing the confusion with an upcoming conference in April on what does, and does not, constitute membership. But expect the ‘threat’ of burgeoning numbers to spark a flurry of warnings of false claims, where some unqualified people simply fill in a form, pay a processing fee (ranging from $10 to $110) and swell the membership rolls as they rush to feed off a tasty settlement from Ottawa.

The concern is that, if there’s a purely financial benefit to somehow be had just from being called “Métis,” everyone will be filing for a Status card to get a piece of that pie. The Métis of BC are taking a shot at minimizing the confusion with an upcoming conference in April on what does, and does not, constitute membership. But expect the ‘threat’ of burgeoning numbers to spark a flurry of warnings of false claims, where some unqualified people simply fill in a form, pay a processing fee (ranging from $10 to $110) and swell the membership rolls as they rush to feed off a tasty settlement from Ottawa.

As I see it, applicants (and those who know they’re Métis) would do well not to expect a real meal. As the Senate experience teaches us, the money’s already been spent on some other dubious identity claims.

Just to add to your list of semi-rhetorical questions… if many cities/towns in Canada were established on lands previously occupied for centuries by Indigenous peoples — precisely because they were such primo spots to reside — but said peoples were kicked off said lands to make way for non-Indigenous purposes, wouldn’t later generations’ effectively returning to those cities/towns actually mean they were on traditional territories — ie living in what are properly seen as their ancestral homelands?