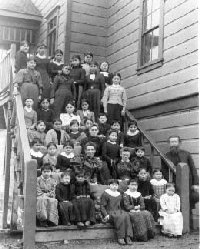

Apprehending First Nations children: a Canadian tradition

An Ontario government report released several weeks ago confirms what many Indigenous people already know: that First Nations children are still vastly overrepresented in Canada’s child welfare systems.

In fact, statistics show that there are more First Nations children in government care today than at the peak of Indian residential schools. In his report, “Children First,” John Beaucage — former Wasauksing First Nation chief and recently-departed Aboriginal Advisor to Ontario’s Minister of Children and Youth Services — calls this generation of child apprehension “the Millennium Scoop,” echoing the wave of apprehensions known as the “Sixties Scoop,” in which thousands of First Nations children were unilaterally adopted or fostered out into non-Indigenous families, often without their families’ or communities’ consent or even knowledge. (That said, Beaucage’s report does note that child welfare systems have changed in that they attempt to ensure that children remain connected to their communities and families, rather than being raised with the explicit assumption or desire that they would assimilate into white society.)

While the federal government apologized for residential schools, there has been no such apology for the continued dismissal of Indigenous sovereignty and our inherent right to care for our own children. In fact, recent agreements about on-reserve health care are said to entail less control by First Nations, and more by the feds, something that has never led to increased opportunity, health or wellness for our children and families in the past. It seems that improving quality of life for First Nations has a price: moving further away from control over our own lives.

I would argue that rather than seeing today’s apprehensions as distinct from those of previous generations, it might be more useful to think about them as part of a historic continuum of government intervention and control. It is difficult to separate the roots and the impacts of the residential school system, the beginnings of the child welfare systems in various provinces across Canada, and the ongoing over-representation of First Nations children in care. At the level of lived experience, many families and communities struggle with the compounding, inter-generational effects of apprehension, separation, and grief. These impacts cannot be parceled out into distinct, distant forms of seizure.

I would argue that rather than seeing today’s apprehensions as distinct from those of previous generations, it might be more useful to think about them as part of a historic continuum of government intervention and control. It is difficult to separate the roots and the impacts of the residential school system, the beginnings of the child welfare systems in various provinces across Canada, and the ongoing over-representation of First Nations children in care. At the level of lived experience, many families and communities struggle with the compounding, inter-generational effects of apprehension, separation, and grief. These impacts cannot be parceled out into distinct, distant forms of seizure.

It is also difficult to separate out these government systems of “caring for” and “educating” our children from other forms of government intervention which together impact the quality of life for First Nations families. At the heart of the matter is Indigenous sovereignty, including our ability to care for our own children and help shape the systems that determine our well-being. Yet mainstream descriptions of the situation, like those found in a July 31 piece by the Canadian Press, blithely assert that “poverty, addiction, history and politics [have] conspired to separate First Nations children from their parents.” It is easy and convenient to blame poverty for conspiring against our children, rather than the people and policies behind systemic poverty. Racism is alive and well in all of the systems that shape the lives of First Nations children: the education system, legal system, health care system, and broader Canadian society. Individuals, including politicians and Canadian citizens, create and perpetuate a society in which the racialized divisions between rich and poor are created and sustained. And those individuals also created and enforce the Indian Act, provincial and federal jurisdictions, policies and programs which determine the quality of life for our children.

Some First Nations, such as the Anishinabek, have drafted their own child welfare law to ensure that their children are being cared for within standards set by their community. However, one challenge facing these efforts is that different approaches are being used within the provinces, as child welfare is determined provincially rather than federally. Struggles over jurisdiction and political power stand at the heart of Indigenous peoples’ control over child welfare, as with other assertions of sovereignty.

Beaucage’s report states that child welfare laws and jurisdictional issues may need to be resolved in order for child welfare to improve. Indeed, he says that “a whole new paradigm shift” is required in order for real change to happen. In my mind, that requires moving beyond or outside of the federal and provincial systems of control, as they perpetuate the very problems they claim to be interested in solving. Luckily for us, we have alternative paradigms in which to make decisions about the well-being of our children: Indigenous law, governance and ways of life. It seems to me that empowering these traditions through assertions of sovereignty is a necessary part of making real change in the lives of Indigenous children and youth in care.

Thank you, Sarah, for your powerful writing and the excellent points you have made here.

My children have been stolen by A First Nation Touchwood Child and family Services. Now they wont tell Me where they are. How do I go about suing them or any help if sumone can help Me locate my children, thank you.