- Introduction

- “An Ink-stained Response to Disrobing the Aboriginal Industry” (Book Review), by N. Sinclair

- Rebuttal to Sinclair review, by F. Widdowson (co-author, Disrobing)

- “Rebutting the Rebuttal: Disrobing Digs Up Debate,” by C. C. Mann (author, 1491)

- “Sewing a shirt on a button: The pseudoarchaeology of 1491,” by F. Widdowson

- Comment on ‘Sewing a Shirt on a Button,’ by C. Powell

- Response to Powell Comment, by F. Widdowson

- “Disrobing the Politics of Cultural Difference,” by C. Powell

- Response to ‘Sewing a Shirt on a Button,’ by C. C. Mann

→ ←

Our first AGENDA INDIGENA debate actually began as a series of posts, first set in motion here on MI by a critical review of Disrobing the Aboriginal Industry: The Deception Behind Indigenous Cultural Preservation, co-authored by Frances Widdowson and Albert Howard.

Over the course of the wide-ranging discussion that has ensued (a tad too widely, some felt), debaters have differed deeply over theoretical understandings and practical implications of culture — in particular, the contentious idea that cultures can and ought to be compared and evaluated against one another. Here, the intellectual and political dispute concerns Canadian policy regarding First Nations governance, a debate that’s been controversially re-ignited by Disrobing the Aboriginal Industry. In this excerpt, the authors note that, “despite billions of dollars being spent,

rates of poverty, substance abuse and violence are much higher for the native population, and that health and educational levels remain far below the national average.

… [T]he reason for [this] massive policy failure is that current initiatives are being formulated and implemented by a self-serving “industry” that works behind the scenes in aboriginal organizations. … The reality of the aboriginal industry is that grievances result in the dispersal of government funds, and so its members benefit from perpetuating, rather than alleviating, aboriginal deprivation.

The aboriginal industry maintains this state of affairs, in part, by advocating cultural traditionalism in the native population. No rational person believes that modern problems can be solved by reverting to the ways of our ancestors, as is assumed in aboriginal policy development. This does not mean that we are prevented from appreciating historical accomplishments, only that we are not obligated to accept all past beliefs and practices under the guise of “preserving our culture.” Valuing the plays of Shakespeare, for example, does not mean that we have to embrace the Divine Right of Kings, blood-letting or burning witches at the stake.

Aboriginal cultural features, however, are perceived as inexorable. It is assumed, for example, that since aboriginal peoples were once hunters and gatherers, they should continue to hunt and trap and gather berries so as to preserve their “spiritual relationship” to the land. Aboriginal languages that are spoken by only a few hundred people should be taught in the elementary grades, we are told, so that aboriginal “worldviews” can continue to find expression. This is not to deny that aboriginal people, like all Canadians, should have the right to pursue the beliefs and cultural practices that give them satisfaction; it is only to stress that this is a choice for individuals to make. The idea that aboriginal peoples are natural hunters, or that they have a predetermined spirituality, is actually a form of racial stereotyping that constrains future possibilities. Aboriginal people, like all other Canadians, can think for themselves.”

→ ←

Certainly, one Aboriginal person who can think for himself is MEDIA INDIGENA’s Niigonwedom Sinclair. It was in fact his review of Disrobing the Aboriginal Industry that begat this entire chain of discussion this past May.

May 16, 2010:

An Ink-stained Response to ‘Disrobing the Aboriginal Industry’

I’ve always hated pencils and erasers.

I’ve always hated pencils and erasers.

I was first forced in grade two to use them, in handwriting class.

My teacher said, “We use pencils and erasers because we’re just learning, and practice makes perfect. This way, we can get rid of mistakes and keep the page clean.”

I loved pens, in all their ink-filled permanency. Black. Blue. Red. Even though I was told not to, every chance I got I filled my scribbler with blots, strokes and smudges. Let the page be messy, I thought. Full of my beautiful, consistent, every-few-seconds mistakes. My errors made my occasional successes that much sweeter.

Even if I did get a D.

Now that I’m grown up, I continue to see pencils and erasers everywhere. And though people are still learning — and hopefully all of this practice is leading somewhere (I’ve given up on perfection) — erasing and keeping the page clean has resulted in some dangerous consequences.

For one example, take Frances Widdowson and Albert Howard’s recently-published Disrobing the Aboriginal Industry: The Deception Behind Indigenous Cultural Preservation. In it, the authors attempt to resurrect widely discredited and blatantly Eurocentric anthropological theories of human “cultural evolution” — first suggested by Edward Tylor (1832-1917) and “refined” by Lewis Henry Morgan (1818-1881) — to argue along progressivist lines that Native societies were “savage,” “neolithic” and “barbaric,” whereas Europeans were at a more complex and advanced “stage of cultural development.” This development gap is evidenced in Aboriginal peoples not having “writing,” the “alphabet,” and “complex government institutions and legal systems” at first contact.

According to Widdowson and Howard, it is the embracing of these “undeveloped” cultures, still steeped in “obsolete features,” that results in today’s Aboriginal peoples having “undisciplined work habits, tribal forms of political identification, animistic beliefs, and difficulties in developing abstract reasoning.” In their parameters — where European historical “development” is the linchpin of all value, complexity, and “civilization” — Widdowson and Howard of course ignore the fact that, while Native communities never had European-based alphabets and governing structures, they did have intricate signification systems (see: Anishinaabeg petroglyphs, Mayan codices, or Iroquois wampum), multidimensional governing institutions (like the Five — later Six — Nations Confederacy, clans/totems, and the “red” and “white” Muskogee Creek town councils), and diverse legal systems (embedded in such principles as reciprocity, mediation, and responsibility), worthy and meritorious on their own terms. [1]

If Widdowson and Howard were simply practicing their Eurocentrism in their own scribblers, they should be allowed to think and write whatever they want. But instead they attempt to influence the rest of us by employing their ‘findings’ to make baffling governmental recommendations, devise a reductionist history, and “solve aboriginal problems.” Although they claim to be attacking the “Aboriginal Industry” (lawyers, consultants, anthropologists and Native peoples themselves) and “a self-serving agenda,” it is clear the authors are most interested in influencing Canadian government policy.

In subsequent chapters, the authors:

- call Native land claims processes delusional, anti-Canadian, and illogical (resulting in further marginalization and isolation from “productivity”);

- declare that the current “accommodation(s)” of “aboriginal practices and beliefs” in the Canadian justice system “actually attempts to prevent justice from being served”; and

- pronounce Aboriginal traditional “knowledge,” “spirituality” and “medicine” anti-scientific, “quackery,” and a pack of “lies.” [2]

They also make similarly arcane points in regards to Aboriginal claims for child welfare, health care, education, and environmental management.

We hope someday you’ll join us…

Everyone, Widdowson and Howard argue, must get beyond the “distortions” that “aboriginal problems were caused by the destruction of viable and ‘sovereign nations’ during European conquest” and heed “objective” research (like theirs) that “proves” that Aboriginal cultures remain “undeveloped” and have little worth in today’s world. They celebrate and defend “the residential school system” as one institution that necessarily facilitated a “civilizing” process where “components of [a] relatively simple culture” were “discarded” and a “more complex” one can enter. [3]

The “fact” is, the authors claim,

“obliterating” various traditions is essential to human survival. Conservation of obsolete customs deters development, and cultural evolution is the process that overcomes these obstacles. … [T]he “loss” of many cultural attributes is necessary for humans to thrive as a species in an increasingly interconnected and complex global system.

Then, in perhaps the most ironic moment of the book, Widdowson and Howard invoke John Lennon’s “Imagine.”[4]

The authors share their “dream” of a time when Native values based in “tribalism,” “kinship relations” and “difference” are eliminated so “we can become a global tribe and the ‘world can live as one,’” a ‘tribute’ that just might have Mr. Lennon spinning in his grave.

With pencil and eraser firmly in hand, and backed by a mainstream university press, Widdowson and Howard have composed an all-too familiar song of assimilation in the name of “progress.”

Their one-dimensional politics, historicism and century-old arguments are known well by First Nations peoples, communities and nations, who continue to endure ongoing attacks on their personal, communal and national sovereignties. The notion that this type of myopia is precisely why the current climate exists and perpetuates itself — not to mention that the authors’ “dream” of more of the same — is found nowhere in their pencil marks.

The truth that, like their western counterparts, expansive Indigenous intellectual systems, languages, governments and cultures change, grow and adjust, and just might have made valuable contributions to “human survival,” “development” and the “interconnected and complex global system” [5] is lost on them.

And if these ideas stopped here, I might too. These authors’ view of Indigenous peoples, their relationship with Canada, and the ways they should “develop” are endorsed by scholars such as Tom Flanagan (author of First Nations? Second Thoughts), political think-tanks such as the Frontier Centre for Public Policy, and by national Globe and Mail columnist Margaret Wente. Their vision is also strikingly mirrored by many practices and policies of the federal governing Conservatives and Prime Minister Stephen Harper, and, sometimes, their predecessors, too.

For example, take the now eleven-year-old cap of 2% on social, education, and economic funding for Native governments and their reserves, the refusal on September 13, 2007 to ratify the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and the reneging on the 2005 Kelowna Accord — an agreement between the federal government and all major Native organizations that was supposed to broker a wave of Indigenous self-determination, economic self-sufficiency and a “new” relationship with Canada — with virtually nothing put in its place.

Or, consider the moves in February 2009 by Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) to radically change post-secondary funding for First Nations students. Essentially, if followed, what has been historically claimed and affirmed as a treaty right by both Canada and First Nations would become a loan-based, provincially-run program. INAC’s “official” explanation: Native students can learn “fiscal responsibility” by taking out loans, “value” education more, and colleges and universities “are not” in “the original wording” of the treaties. The change in policy directives has expectedly been met with tremendous backlash.

There are other examples in other arenas. Go to any major department or new-age store. There you’ll find air-fresheners, souvenirs, and toys dressed up in colourfully painted, plastic and chicken-feathered headdresses, dream catchers, and smudge kits, with complete instructions on how “real” Indians use them.

There are other examples in other arenas. Go to any major department or new-age store. There you’ll find air-fresheners, souvenirs, and toys dressed up in colourfully painted, plastic and chicken-feathered headdresses, dream catchers, and smudge kits, with complete instructions on how “real” Indians use them.

Like static, archaic and empty relics, these items are easily explained, objectified and (most importantly) cheap. Erased are the historical, intellectual, and political significance of these items — treated as if legal, governmental and social contexts and ownerships can be extracted, removed or fixed in a tragic, disappearing past. Put in their place are ridiculous notions of authenticity — as if Native expressions and ideas haven’t changed in centuries.

Want others? Try the reality that there are no federally-recognized Indigenous language rights in Canada, while French and English enjoy protection, support, and money in all of their “official status” glory. Consider the fact that when Indigenous peoples defend their claims to territories and land they are labeled in the media and the public as illegal “squatters” interested in “anarchy” and “violence” (see: Oka, Caledonia, and protests against the Vancouver-Whistler 2010 Olympic construction projects). Think about how most ordinary Canadians don’t know that they are standing on treaty land right now, or that all of us benefit from treaties, or that each of us have ongoing responsibilities to uphold obligations as parts of these agreements.

I state all of this to show that Widdowson and Howard, while egregious in their claims, are not alone. While many have (rightfully) focused their efforts on engaging and upending their simplism, there is simply much more work that needs to be done. One-sided stories, erasure, and a landscape free of Native claims of sovereignty, land, and historical contributions still make up the bulk of North American culture. It’s the norm.

When people speak up and insist on Canada’s messy past being raised, discussed, and recognized, they are labeled ‘separatists,’ ‘angry’ and accused of perpetuating ‘falsehoods’ and ‘delusions’ — often to avoid responsibly and ethically engaging with their ideas. Then attempts are made to clean up the page, as Native peoples and their allies are ironically asked: “Why can’t you just be happy that Canada allows you to live, speak, and be free?”

Some change is happening. For all of the myopia and self-imposed ignorance embedded in these discourses, there is also responsible, ethical, and well-researched scholarship — most of which is provocative, rich, and multi-layered in its complex and diverse treatment of Indigenous peoples, communities, issues. Work produced by Native scholars in Canada such as Cheryl Suzack, Daniel Heath Justice, Deanna Reder, Kristina Fagan, John Borrows, Emma Laroque, Olive Dickason, Neal McLeod, Bonita Lawrence, Glen Coulthard, Chris Anderson, Jo-Ann Episkenew, Paul DePasquale, Linc Kesler, David Newhouse and Leanne Simpson (just to name a few) and non-Natives such as J. Edward Chamberlain, Peter Kulchyski, Arthur Ray, Daniel Francis, Sam McKegney, Margery Fee, Gordon Johnston, Keavy Martin, Daniel Morley Johnson and Renate Eigenbrod are models we should aspire to as responsible scholars and ethical researchers. Their work proves that all Canadians can partake in, learn from and engage with Indigenous histories, practices and intellectualism to make the spaces we share meaningful, respectful and beneficial for all. Change is slow, but it’s happening.

With all ideas, practices, and policies — ones we agree with and ones we don’t — Native Studies scholars must thoroughly interrogate and question our underlying claims, use reputable evidence to support our own, and always encourage honest and informed dialogues and debates among thinkers of diverse political and ideological opinions. Of course, this will result in spirited discussion, for these issues are about our collective futures and relationships as Native peoples, Canadians, immigrants — and sometimes all three.

We must therefore adopt, both personally and in our scholarship, a principle of respectful inter-responsibility embodied in the notion that we are ultimately neighbours, colleagues, and partners in this shared space called Turtle Island, or North America. We must also remind ourselves, and others, that Native nations and Canada, both historically and today, are more interrelated, interconnected, and reliant on one another than people tend to remember, recall, and conceptualize. “We are a métis civilization,” as John Ralston Saul writes in A Fair Country: Telling Truths about Canada, a people influenced by over five centuries of contact, influence, and growth with one another, and “[t]his influencing, this shaping is deep within us.”

And there’s something else we can do. Use our pens.

Rather, we can perceive the world and, in the ink of that knowledge, express our thoughts. We can speak of the beautiful ugliness in the history of this land. Insist on the permanency of Indigenous homes here. Reflect upon all of the nations and treaties that make up these spaces. Theorize Indigenous, settler, and Canadian intellectual histories, while recognizing that each have specific, rich, and important epistemologies, contributions, and histories that can dialogue. Sing about our interactive experiences, and ultimately learn from one another. Share stories, reflect, and listen— always listen.

And we can — perhaps most of all — make, accept, and cherish the messy blots, strokes, and smudges of our experiences on this earth, on these streets, in this life. Insist on this — even if it seems difficult, strenuous, and stressful — because this changes the world. Years of resistance and courage in the face of erasure, for example, is what made the 2008 Indian Residential School Apology happen. These tenets of Indigenous life are, in fact, why all of us are still here.

No matter how many professors, politicians, and citizens say that Aboriginal peoples, communities, nations are simple, static, and “dying,” as long as we do these things, Indigenous futures — and in turn our collective diversity, interests in equality, and inter-relationships with one another — will be ensured. I guarantee it.

The preceding piece originally appeared in somewhat different forms in guest editorials/commentaries for Kanata (Vol. 1) and Canadian Literature: A Quarterly of Criticism and Review in its Winter 2009 (#203) issue.

FOOTNOTES

1. For reputable and detailed research on this, I recommend Charles Mann’s 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus, or Arthur Ray’s I Have Lived Here Since the World Began: An Illustrated History of Canada’s Native People as excellent starting points.

2. This is only a minor sampling of these authors’ grandiose statements and recommendations. For more, see chapters entitled “Land Claims: Dreaming Aboriginal Economic Development,” “Self-Government: An Inherent Right to Tribal Dictatorships,” “Justice: Rewarding Friends and Punishing Enemies” and “Traditional Knowledge: Listening to the Silence.”

3. Widdowson and Howard claim that when Native peoples and their advocates label the “missionaries’ efforts as ‘genocide’” this “obscures” the reality that residential schools were important movements in Native “cultural development.” Although they admit that “the missionaries deserve criticism for the methods they employed in attempting to bring about this transition,” they claim that “[m]any of the activities held as destructive to aboriginal peoples — the teaching of English, the discouraging of animistic superstitions, and encouraging of self-discipline — were positive measures intended to overcome the social isolation and economic dependency that was (and continues to be) so debilitating to the native population.”

4. The use of the song by Widdowson and Howard is ironic on several levels. “Imagine,” which appeared as the title track on John Lennon’s 1971 number-one album, is widely known as holding an anti-war, anti-violence, anti-religious, and anti-capitalistic message, which doesn’t quite mesh with the authors’ Eurocentric, assimilationist agenda, nor the interest in such violent policies as residential schools. In addition, the fact that historically the song was written in response and resistance to the Vietnam Conflict — a war devised out of nationalistic, patriotic, and ideological conformity, not to mention the deaths of 6 million people and a long-standing occupation by Americans — and experiences that virtually mirror Aboriginal peoples’ in North America, seems lost on the authors. Or, perhaps Widdowson and Howard are literally interested in Lennon’s intentions, as envisioned and embodied in his music video of “Imagine.” It features a cowboy-dressed John Lennon walking through a forest, holding hands with a stoic and Pocahontas-looking Yoko Ono, when the two discover a beautiful house, enter a room completely painted white, and a timid Ono sits mutely while Lennon sings (ending only when he decides to kiss her).

5. For more provocative ideas and opinions on Indigenous perspectives on, and potential contributions to, globalization and world economic development, see Jerry Mander and Victoria Tauli-Corpuz’s edited collection of essays and opinions by twenty-seven scholars and activists from across the world, Paradigm Wars: Indigenous Peoples’ Resistance to Globalization.

[ Images via (busy), AmySof, photobunny]

→ ←

Return to

Table of Contents

→ ←

After Sinclair’s critical review of Disrobing, one of its co-authors, Frances Widdowson, offered this response.

June 14, 2010:

Co-Author of ‘Disrobing the Aboriginal Industry’ Pens Her Rebuttal

I appreciate Niigonwedom Sinclair’s efforts in reviewing the book I co-wrote with Albert Howard. Although I find most of Sinclair’s opposition to our work to be rooted in wishful thinking, and almost all the claims that he makes remain unsubstantiated, the opportunity to have this civil exchange is important: no one has a monopoly on the truth, and by honestly stating what we believe is true, and striving to objectively evaluate the evidence available, everyone can develop a more complete understanding of reality, including the nature of aboriginal/non-aboriginal relations.

I appreciate Niigonwedom Sinclair’s efforts in reviewing the book I co-wrote with Albert Howard. Although I find most of Sinclair’s opposition to our work to be rooted in wishful thinking, and almost all the claims that he makes remain unsubstantiated, the opportunity to have this civil exchange is important: no one has a monopoly on the truth, and by honestly stating what we believe is true, and striving to objectively evaluate the evidence available, everyone can develop a more complete understanding of reality, including the nature of aboriginal/non-aboriginal relations.

Particularly refreshing is the fact that Sinclair does not engage in any personal attacks, or deploy the usual accusations of “racism,” “colonialism,” etc., to try to stifle debate on these issues. The only label that he uses is “Eurocentric” — an orientation that could be defended, depending upon one’s view of the economic, political and intellectual advancements that have occurred in this region historically. Sinclair’s major concern, as it should be, is about the accuracy of our work. In his opinion, the theory of cultural evolution that we use has been “discredited,” our recommendations are “baffling,” and the claims made are “egregious.”

In his critique of our book, Sinclair encourages “Native Studies scholars” to

thoroughly interrogate and question … underlying claims, use reputable evidence to support [their] own, and always encourage honest and informed dialogues and debates among thinkers of diverse political and ideological opinions.

Although this sentiment is commendable, to what extent is Sinclair practicing what he preaches? Has he “thoroughly interrogat[ed]” the argument that the theory of cultural evolution has been “discredited”? Although people like Taiaiake Alfred and Peter Kulchyski have said so, they have not really shown how this is the case.

The theory of cultural evolution has, in fact, been implicitly accepted in the discipline of archaeology, in the division of human history into the Stone, Bronze and Iron ages. It is also generally understood that food production evolved out of hunting and gathering (what Morgan generally referred to as the stage of “savagery”), and industrialization was made possible by food production. Therefore, what aspects of the theory is Sinclair contesting?

It also should be stressed that the theory of cultural evolution, and its conception of earlier developmental stages, does not just refer to “Native societies”: all human beings were, at one time in history, “’savage’, ‘neolithic,’ and ‘barbaric.’ Characterizing societies in this way is based on the technology present at the time, not on some kind of European “value” or a conception of particular cultures being “worthy or meritorious.” Whether one values something or not depends upon its contribution to human survival.

In addition, it is not our view that aboriginal cultures are “static,” but that their capacity to “change, grow and adjust” is hindered by Aboriginal Industry initiatives that encourage the native population to look to the past for answers to current problems. Respect for “tradition” is a mantra in aboriginal policy, and we are arguing that tradition should not just be accepted for its own sake, but on the basis that it can provide a social contribution.

In other words, we are opposing atavism in culture, not adaptation and integration. Our point is not to deny that aboriginal cultures developed historically: rather, it is that, because of historical accident — namely, the absence of the necessary plants and animals in the Americas (wheat, for example), plus the north-south alignment of the continent — aboriginal cultures developed at a slower rate than what was possible in parts of the Old World.

Wishful thinking does not constitute legitimate criticism

If Sinclair is serious about using “reputable evidence” to support his claims, he should take a critical look at Charles C. Mann’s 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. Sinclair, like many aboriginal commentators, is enthralled with this work because it supports his preconceptions about the “sophistication” of pre-contact native tribes.

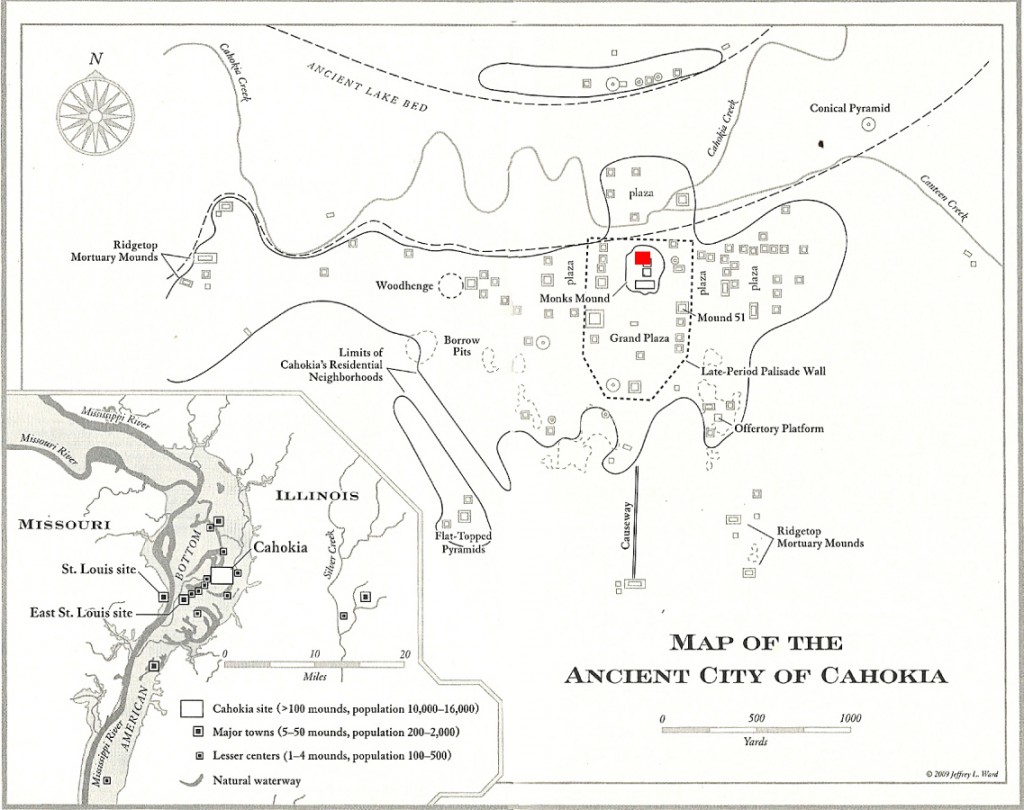

Advocates for atavism in aboriginal life disregard the hugely speculative content of Mann’s writings. Take, for example, one of Mann’s flights of imagination about life on the Mississippi in 1100 A.D. In this account, we marvel at the “city” of Cahokia with its population of fifteen thousand people and

carefully located fields of maize; and hundreds of red-and-white plastered wood homes with high-peaked deeply thatched roofs like those on traditional Japanese farms.

What was the technology that allowed for such accommodation? We are informed that the maize was weeded with stone hoes, but how were the homes built without saws or nails? What about the red and white paint? His claims of these fantastic developments include that “Cahokia was a busy port,” even though the Stone Age technology present would only have been able to produce small boats limited in the distances they could travel (making a “busy port” unlikely in this context).

It should at least be recognized that Mann’s speculations with respect to Cahokia are exclusively based on the existence of large mounds of earth found at the confluence of the Missouri, Illinois and Mississippi rivers, the source of which is debated — either they were built (for no understandable reason) or they are natural formations.

Sinclair also might want to critically investigate the claim he made that pre-contact native communities had

intricate signification systems (see: Anishinaabeg petroglyphs, Mayan codices, or Iroquois wampum), multidimensional governing institutions (like the Five — later Six — Nations Confederacy, clans/totems, and the ’red’ and ‘white’ Muskogee Creek town councils), and diverse legal systems (embedded in such principles as reciprocity, mediation, and responsibility) …

One of the sources used to support this statement is Mann’s 1491. But it is not clear, for example, that wampum can be “read,” as is claimed by many Native Studies scholars. This is shown in a case recounted by John Borrows, where the “self-proclaimed interpreter of wampum belts,” Stephen Augustine, declared that a belt of wampum was an ancient Mi’kmaq “constitution.” A rigorous review of the evidence showed that the “belt” was actually a shawl that was created by a Quebec aboriginal group so that a gift could be provided to the Pope.

Sinclair discusses many circumstances that he claims are responsible for the difficulties being faced by aboriginal communities — a violation of treaty rights, the lack of recognition of indigenous languages and changes in aboriginal post-secondary funding. There is no attempt, however, to show how these policy changes have exacerbated aboriginal marginalization.

A number of aboriginal scholars are referred to as engaging in “responsible, ethical, and well-researched scholarship,” and it is argued that “their work proves that all Canadians can partake in, learn from and engage with Indigenous histories, practices and intellectualism to make the spaces we share meaningful, respectful and beneficial for all.” But, once again, Sinclair does not show how this is the case.

There are many instances in the field of Native Studies where critical works are avoided and the unquestioned acceptance of methodologies such as “oral histories” have resulted in erroneous claims being disseminated. The most disturbing refusal to “thoroughly interrogate and question … underlying claims” concerns the denial of the Bering Strait theory in the face of extensive and reputable archaeological, linguistic, and genetic evidence.

Although I have not examined all the authors Sinclair refers to, I am familiar with the work of one Native Studies scholar he praises — Leanne Simpson. I would be interested in how her work could be considered “well-researched.” One recent article of hers refers to a “nation-to-nation” relationship between fish and human beings on the basis that weirs existed historically — a nonsensical proposition that assumes that all species are “nations” and that the killing of animals constitutes a “relationship.” Simpson also constantly uses references to her own work to support highly contentious arguments — a practice that is considered to be unscholarly.

In conclusion, Sinclair is right in his demand that scholarship must be rigorous and fair to other points of view. Although Disrobing the Aboriginal Industry could have incorporated additional data, and some errors in such a wide ranging critique are inevitable, we did engage with opposing arguments, and tried to provide evidence for all the claims that were made. More importantly, unlike many researchers working in the area of aboriginal policy today, we were not paid to produce a particular point of view; the book was produced without the benefit of any outside funding, and so we were not beholden to any interest.

We wrote the book because we thought our ideas were true, not because we were the hired guns of government or an aboriginal organization. If Sinclair really is interested in critiquing our work — and not just dismissing an inconvenient truth — he should investigate the particular claims that we have made and show how they are inconsistent with the historical evidence that is available.

→ ←

Return to

Table of Contents

→ ←

After learning of Frances Widdowson’s criticism of 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus, specifically, her dispute with its account of the ancient Cahokia mounds site (located in what is now the US state of Illinois), Charles C. Mann (1491‘s author) responded.

In her rebuttal, Dr. Widdowson wrote:

Take, for example, one of Mann’s flights of imagination about life on the Mississippi in 1100 A.D. In this account, we marvel at the “city” of Cahokia with its population of fifteen thousand people and [writes Mann] “carefully located fields of maize; and hundreds of red-and-white plastered wood homes with high-peaked deeply thatched roofs like those on traditional Japanese farms.”

What was the technology that allowed for such accommodation? We are informed that the maize was weeded with stone hoes, but how were the homes built without saws or nails? What about the red and white paint?

His claims of these fantastic developments include that “Cahokia was a busy port,” even though the Stone Age technology present would only have been able to produce small boats limited in the distances they could travel (making a “busy port” unlikely in this context).

It should at least be recognized that Mann’s speculations with respect to Cahokia are exclusively based on the existence of large mounds of earth found at the confluence of the Missouri, Illinois and Mississippi rivers, the source of which is debated — either they were built (for no understandable reason) or they are natural formations.

I must confess that I was surprised to hear that Dr. Widdowson considers that the mounds at Cahokia might be “natural formations.” Literally hundreds of archaeological papers say otherwise.

If she is curious to learn more, she might read any of the important Cahokia books, including:

- Cahokia: Ancient America’s Great City on the Mississippi, by Timothy R. Pauketat

- Cahokia, the Great Native American Metropolis, by B. W. Young and M. L. Fowler

- Cahokia and the Hinterlands, editors, T. E. Emerson and R. B. Lewis

- The Cahokia Atlas, by M. L. Fowler

These are not “fringe” works, in any sense. Nor were their authors on the margins of scholarship. Fowler was, until his retirement, a prominent archaeologist at the University of Wisconsin; Pauketat is at the University of Illinois; the volume by Emerson and Lewis contains work by well-known researchers from across the country.

The question of whether Cahokia is anthropogenic or “natural” is so thoroughly settled that I suspect one couldn’t find a single peer-reviewed journal article asserting this point written in the last 80 years. Indeed, the popular science writer Robert Silverberg wrote an entire book about the controversy, which ended in the nineteenth century (it’s cited in 1491).

The question of whether Cahokia is anthropogenic or “natural” is so thoroughly settled that I suspect one couldn’t find a single peer-reviewed journal article asserting this point written in the last 80 years. Indeed, the popular science writer Robert Silverberg wrote an entire book about the controversy, which ended in the nineteenth century (it’s cited in 1491).

Dr. Widdowson quotes my description of Cahokia (p. 284), calling it one of my “flights of imagination.” From this, I gather she believes I made this stuff up. Had she looked at the endnotes, she would have found the source of that particular description: the five-author volume, Envisioning Cahokia (pp. 64-78). Had she gone to the library and looked at Envisioning, she would have learned, among other things, that J.R. Swanton‘s classic The Indians of the Southeastern United States — hardly an obscure source — has a lengthy description of research on Mississippian pigments and house colors, including those at Cahokia. She would also have learned that the first archaeological research at Cahokia using modern techniques, conducted by Harriet Smith in the 1940s, uncovered scores of wattle and daub houses. Hundreds more have been identified since then.

Wattle and daub houses are made by interlacing poles to create a wall (the “wattle”) that is filled in with mud mixed with grass and straw (the “daub”). It’s an excellent building material — indeed, it was quite common in Europe at the same time, with English houses as late as the Tudor period having wattle-and-daub walls. (Incidentally, this is but one of many ways that “homes were built without saws or nails” — metal saws and nails did not become common home-building tools in Europe until the seventeenth century.)

Unfortunately, wattle-and-daub is not especially good for floors, so the Cahokians used plaster — at least the most wealthy did. Pauketat, for instance, excavated the 17 large homes atop Kunneman Mound and found they had red, black, and yellow plaster floors. In the photographs, as I recall, some of the color is still quite clear.

If Dr. Widdowson would like, I could send her many citations for the remains of thatched roofs, and the evidence of peaked roofs, hipped roofs, gabled roofs, etc., at Cahokia. But all of this is what I meant by referring to plastered houses with thatched roofs.

Was Cahokia a busy port? Let me quote Fowler in The Cahokia Atlas (p. 201):

There was nothing like Cahokia for hundreds of miles, and even then its rivals were but pale reflections. People from as far away as the banks of the Wisconsin River to the north and the Red River to the south, the southeastern edge of the Great Plains, the Southern Appalachians, the Ohio River Valley, and the upper reaches of the great Missouri River all came to Cahokia with their special goods to trade or to pay homage to the power and rulers of Cahokia.

To me, this sounds like a busy port.

As for the idea that small boats with “Stone Age technology” cannot go very far, fortunately, it seems not to have discouraged the peoples who regularly went up and down the 3500-mile-long Amazon (you can go to the Goeldi museum at Belem, at the river’s mouth, and look at the goods from the Andes that were excavated from nearby archaeological sites).

What’s important is that here I am citing the most mainstream, dully conventional archaeological work. This is what you learn if you take Mississippian Societies 101.

The material in my book is not “exclusively based on the existence of large mounds of earth” but on decades of fine scholarship and hard work by dozens of researchers. As I said, I have not read Dr. Widdowson’s book and know little of her work. But it does not give me confidence that she is apparently willing to publish assertions that a simple Google search would have disproven.

[ Image of Cahokia artifact via enjoyillinois.com ]

→ ←

Return to

Table of Contents

→ ←

Widdowson counter-responds to Mann.

Aug. 30, 2010:

Sewing a shirt on a button: The pseudoarchaeology of 1491

In my response to Niigonwedom Sinclair’s review of Disrobing, I questioned Sinclair’s use of Charles C. Mann’s 1491 as a source. My discussion of Mann, unfortunately, was not based on an in-depth examination of his work, or the evidence that Mann used to support his assertions. There is also an error in my statement that “Mann’s speculations with respect to Cahokia are exclusively based on the existence of large mounds of earth.” The word “exclusively” is too categorical a term, and “largely” would have been a better description. Finally, my poetic reference to Mann’s “flights of imagination” was not meant to imply that Mann “made this stuff up.” As will be discussed in further detail below, it refers to Mann’s tendency to “sew a shirt on a button” – that is, to make highly speculative and improbable claims on the basis of very scant archaeological evidence.

In my response to Niigonwedom Sinclair’s review of Disrobing, I questioned Sinclair’s use of Charles C. Mann’s 1491 as a source. My discussion of Mann, unfortunately, was not based on an in-depth examination of his work, or the evidence that Mann used to support his assertions. There is also an error in my statement that “Mann’s speculations with respect to Cahokia are exclusively based on the existence of large mounds of earth.” The word “exclusively” is too categorical a term, and “largely” would have been a better description. Finally, my poetic reference to Mann’s “flights of imagination” was not meant to imply that Mann “made this stuff up.” As will be discussed in further detail below, it refers to Mann’s tendency to “sew a shirt on a button” – that is, to make highly speculative and improbable claims on the basis of very scant archaeological evidence.

The cursory character of my rebuttal provoked some justified critical comments from Mann himself, as well as a few readers of mediaINDIGENA. It is encouraging to see such criticisms being put forward, as it indicates that there is a certain amount of interest, amongst those who study aboriginal-non-aboriginal relations, in attempting to come to a universal understanding of what happened historically. Mann and mediaINDIGENA readers are not employing pervasive postmodern Native Studies arguments about culturally relative indigenous “ways of knowing”; they are maintaining that 1491’s version of history is universally applicable, and therefore it should be accepted by everyone (including “westerners” like me).

If readers are intellectually honest in their quest for knowledge, however, they should be wary of being predisposed to uncritically accept views that they want to believe. A few comments in support of Mann’s rebuttal, for example, indicate that some have an emotional stake in the arguments being put forward in 1491. Why should people care one way or another what Cahokia was like between 950 and 1250 A.D.? The population, dwellings, modes of transport, etc., that existed in the American Bottom one thousand years ago is a scientific question, and one’s conception of this society should flow from the evidence that is available (largely from archaeological findings).

Many people today, especially those in the Native Studies field, however, are predisposed to accept Mann’s ideas because they challenge the theory of cultural evolution. They are enthusiastic supporters of Mann’s view that “the complexity of a society’s technology has little to do with its level of social complexity.” [1] They do not see the absence of technology such as the plough, the wheel, draught animals and metallurgy (i.e., the extraction of minerals from their ores) as constraining the level of social development in the Americas before contact, and, like Mann, they would argue that the size and sophistication of these cultures are much greater than was previously thought. [2]

They would applaud Mann’s comparison of prehistoric Stone Age American societies with Iron Age civilizations such as Ancient Greece, [3] the cultures of European colonists [4] and even societies existing today. [5] Mann’s contention that Cahokia would be considered a “civilization” if its “ruins” were found “anywhere else in the world” [6] would be appreciated by those attempting to assert that all cultures across time and space are equally evolved, just “different.”

There is a tendency to state that all aboriginal societies in the Americas were civilizations because otherwise they could be logically assumed to be “uncivilized.” [7] But such comparisons ignore the technological basis of the classifications that have been developed in archaeology over the last hundred and fifty years (the three-age system).

Occasionally, one sees higher population densities than would be expected given the level of technology, due to particularly fertile environments, but monument building would have been less developed due to technological deficits. In the case of Cahokia, for example, one has to consider the technology that existed and how the society being examined could have produced the food it would have required to sustain itself, while at the same time having the manpower to build the “ruins” of this “civilization” that Mann claims existed. [8]

How would it have created the agricultural surplus necessary to free up the people required for mound building, palisade erection (consisting of 20,000 logs that had to be constantly replaced), the construction of thousands of red waddle and daub houses with red, yellow or black plaster floors and peaked, hipped or gabled roofs, and the deliberate cutting, filling and leveling of a fifty-acre plaza, as well as building and servicing boats regularly traveling thousands of miles and thus filling a “busy port”?

In another section of 1491, Mann himself recognizes a technological deficit in discussing the problem of using stone axes to fell trees. He refers to the research of Robert L. Carneiro, who found that it took 115 hours to fell a single tree with a stone axe when a steel axe required less than three hours. [9]

Mann even has the audacity to compare the size of Cahokia to the city of London, England. [10] But numerous monuments in London in 950-1250 AD are known to have existed at this time — the London Bridge, the Tower of London, Westminster Abbey, and Saint Paul’s Cathedral, to name a few [11] — testifying to its dense population. This differs from the “ruins” (i.e., building remnants) in Cahokia, which exist only on the basis of questionable inferences by Cahokianists and “artist’s reconstructions.” [12]

It also has been shown that the density of the population in London was due to advances in field agriculture that occurred in England, as well as Iron Age technological developments. [13] Furthermore, there are extensive written records of the development of trade, legal systems, institutions of governance, and education. Since a written alphabetic language existed, schools were involved in teaching grammar, rhetoric and logic, as well as examining the translated works of Euclid, Ptolemy, Galen, Hippocrates and Aristotle. [14]

It is important to stress that the city of London was very different from the outlying villages. These villages contained about 300 people in the 13th Century and “small houses clustered around the great stone church, its narrow streets radiating from the village green, its mill, its alehouse, and perhaps a manor house”. Each house had a garden and open fields stretched into the distance. [15] This indicates that huge differences existed between the town and the countryside in the development of Old World civilizations.

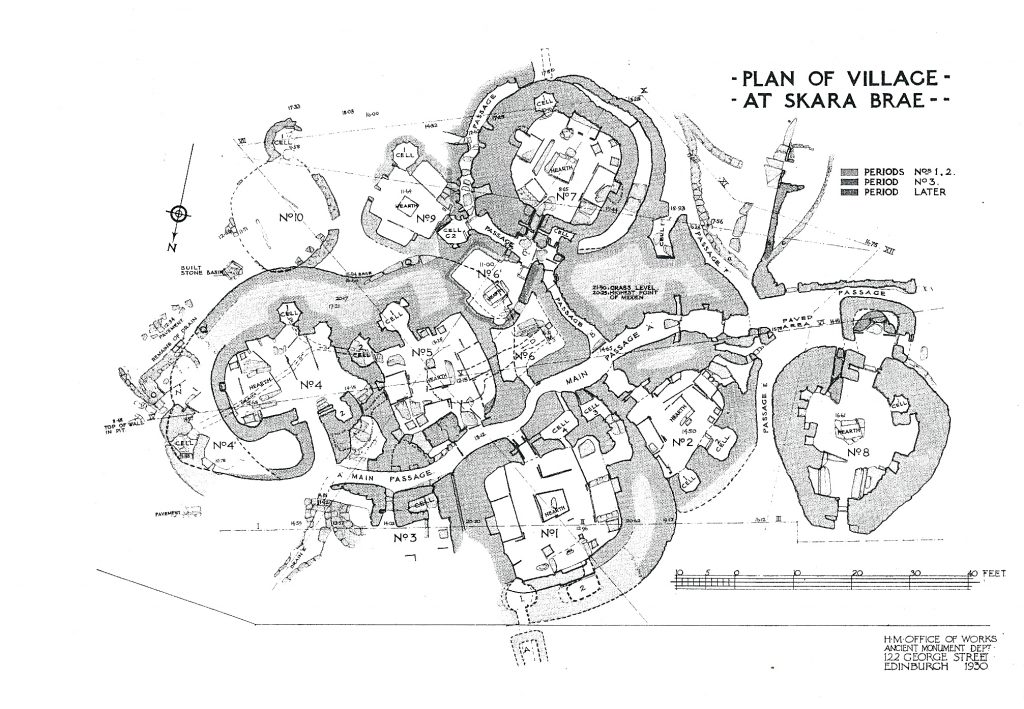

Rather than comparing Cahokia with London, a much better parallel would have been the megalithic cultures in Malta, Portugal, Denmark and England. The huts of Skara Brae, a Neolithic village in the Orkney Islands that existed over 3,000 years ago, would also provide a fruitful comparison (although this culture also incorporated stone into its dwellings, not just wood, soil, and dried grasses/reeds/leaves). Many megalithic cultures piled earth in a round mound over burials with grave goods. [16] Although these societies had relatively equivalent technology to Cahokia in their early stages, they underwent profound changes in 1400 BCE in conjunction with developments in bronze metallurgy that would have made them more productive.

Although an investigation of the similarities and differences between early European Neolithic cultures and those that existed in the American Bottom would appears to be more logical than attempting to draw correlations with the much larger, technologically advanced, and economically productive city of London in 950-1250 AD, such comparisons are avoided by Mann. This is because 1491 is influenced by a political agenda that is common in Native Studies — denying the developmental gap that existed between aboriginal and European societies before contact. As such, Mann is more of an advocate than a scientist, which leads him to be a purveyor of what Garrett G. Fagan has referred to as “pseudoarchaeology.”

Pseudeoarchaeology, according to Fagan, differs from scientific archaeology in that it selects evidence to support a preconceived conclusion. As a result, the pseudoarchaeologist constructs “a jerry-built scaffold of possibilities reflecting what the speculator thinks the past should look like, rather than a solidly evidenced reconstruction of what it may actually have looked like.” [17] Although generally this trend is found in books written for the public, like 1491, professional academics can also be susceptible to this tendency when “egos, ideologies, or other personal beliefs get in the way of their commitment to honest inquiry.” [18]

Pseudeoarchaeology, according to Fagan, differs from scientific archaeology in that it selects evidence to support a preconceived conclusion. As a result, the pseudoarchaeologist constructs “a jerry-built scaffold of possibilities reflecting what the speculator thinks the past should look like, rather than a solidly evidenced reconstruction of what it may actually have looked like.” [17] Although generally this trend is found in books written for the public, like 1491, professional academics can also be susceptible to this tendency when “egos, ideologies, or other personal beliefs get in the way of their commitment to honest inquiry.” [18]

Fagan outlines a number of characteristics of pseudoarchaeology that can help to identify it, including the “appeal to academic authority,” making “huge claims” that findings are “spectacular and history-altering,” “vague definitions,” “selective and/or distorted presentation,” and recounting legends and myths “as accurate accounts of historical events.” [19]

Fagan also points out a number of rhetorical strategies used by pseudoarchaeologists. The most significant is when “suggestions are raised as possibilities in one place and resurrected later as established facts.” As Fagan points out, “pseudoarchaeology begins with a known quantity and stretches it into the unlikely to conclude the implausible. What is conceivable trumps what is demonstrable.” [20]

N.C. Flemming makes a similar point when he notes that “pseudo-writings repeatedly rely for their effect on the assertion that ‘A could be so, and, if this is accepted, B could be true also.’ The alternatives are not checked, and the concepts of greater probability, greatest logical simplicity, or greatest elegance are not even considered. The probability that the first proposition ‘A’ could actually occur (or be wrong) is not estimated.” [21]

All of these indicators of pseudoarchaeology can be seen in varying degrees in 1491. More distressingly, some of these characteristics are also present in a number of the archaeological sources Mann uses — especially the works of Timothy R. Pauketat (Cahokia: Ancient America’s Great City on the Mississippi), Melvin L. Fowler (The Cahokia Atlas), William I. Woods’ unpublished papers (as cited by Mann), and the book Envisioning Cahokia by Rinita Dalan et al.. Particularly noticeable in these works is the “exaggerated and persuasive nature” of the pseudoarchaeological language used, in contrast to scientific writing that values “a deadpan factual presentation with the highest degree of simplicity and clarity.” [22]

With these concerns about the possibility of pseudoarchaeology noted, I am now in a position to investigate Mann’s claims about Cahokia in detail. I will do so by examining the available archaeological evidence with respect to the following four questions:

1) Was Cahokia a “city” of 15,000 people?

2) Were the mounds in Cahokia constructed by human beings?

3) What were the dwellings in Cahokia like?

4) Was Cahokia a “busy port”?

These questions cannot just be answered by an appeal to authority, as is largely Mann’s approach in his rebuttal, since this is an indicator of pseudoarchaeology.

1. Was Cahokia a “city” of 15,000 people?

In his response to my rebuttal, Mann does not address my objection to this characterization (made in 1491). Mann refers to Cahokia as a “city” even though he maintains that “it is not a city in the modern sense.” [23] He goes on to say that “Cahokia’s dissimilarity” is due to “having never seen a city its citizens had to invent every aspect of urban life for themselves.” The use of the word “city,” therefore, appears to rely on a vague definition, as occurs in pseudoarchaeology.

As Mann claims that he has “tried to use terms that historians of Europe or Asia would use to describe social and political entities of similar size and complexity,” [24] questions should be asked as to what constitutes a city in the archaeological literature. An archaeology textbook on ancient civilizations, for example, notes that there are three characteristics of a city:

1) a relatively large and dense settlement

2) the development of specialization and interdependence between the urban core and rural hinterland (the former is characterized by craft manufacture and markets where products can be exchanged)

3) “a degree of organizational complexity” consisting of “centralized institutions to regulate internal affairs and ensure security”

These centralized institutions are indicated by monumental architecture such as fortifications, temples and palaces. [25]

With respect to the large size and density of Cahokia, it is highly unlikely that thousands of people lived in this area. Population estimates should be tempered, in part, by looking at societies with similar technology and infrastructure. It has been already mentioned that English villages of the 13th Century, with much more sophisticated technology, only contained about 300 people. The evidential support for the 15,000 number is sparse: it is maintained that it would have taken a “big workforce” to have constructed Monks Mound quickly, which Woods, for example, hypothesizes was necessary to ensure that the mounds would not succumb to slumping. [26]

Pauketat makes a similar argument with respect to his interpretation that the grand plaza was leveled in a short space of time, even asserting that the “city” of Cahokia emerged as a “big bang” where “political and social change happened quickly, effected by visionaries who shaped events and influenced a group of people in a profound way…” [27] These assertions are purely speculative, however, and one would have to consider that it is unlikely that the number of people needed to construct earth mounds and “plazas” would exceed the number required for creating Stonehenge (dragging large rocks would have necessitated much more coordinated efforts).

With respect to the second characteristic of a city, there is very little evidence of specialization and interdependence between the core and hinterland in Cahokia, despite arguments to the contrary. While both Pauketat and Fowler refer to craft manufacture, and Fowler maintains that markets “may have been held,” [28] the only “crafts” referred to are shell beads, microlithic artefacts and sandstone files. [29] The evidence of a division of labour is very weak, therefore, and it is hard to accept that markets existed when there was no currency or writing. No interdependence between urban and rural in Cahokia is indicated by the archaeological record since the dwellings in Cahokia did not differ functionally from those outside “the downtown”; “temples” are often mentioned, but it is not explained how one can differentiate a temple from a residential dwelling (no altars or offering tables are noted). Although social stratification is shown by the grave goods that were buried with skeletons, there does not appear to be a higher-density manufacturing centre with farmers residing in the outlying areas. Mann, in fact, maintains that Cahokia consisted almost exclusively of farmers, and that “it had few specialized craftworkers and no middle-class merchants.” [30]

A number of aspects of organizational complexity are put forward — a palisade requiring 20,000 logs, woodhenges (“astronomical observatories,” in Pauketat’s words), and large plazas. This infrastructure does not exist as “ruins,” however; it has been interpreted through aerial photography, the excavation/analysis of impressions in the soil and geophysical surveys. Although determining the archaeological validity of these claims would require a deeper analysis than what is possible here, it is important to note that many of the assertions made by Cahokianists follow the pattern noted by Fagan — “suggestions are raised as possibilities in one place and resurrected later as established facts.”

In the case of the palisade, for example, its existence has been inferred from a line of differently coloured soil, from which a trench was intermittently excavated to the east of Monks Mound. [31] Although it is recognized that only “the eastern portions of this palisade were clearly indicated on the air photos and in the limited excavations,” [32] Cahokianists who note this go on to assume that there was a western, southern and northern wall; it is even present in the “reconstructions” of “downtown Cahokia” that appear in figures and illustrations. This “fact” is then enthusiastically recounted by Mann who asserts that “a massive, two-mile-long palisade around the central monuments, complete with bastions, shielded entryways, and maybe a catwalk up top” was constructed. He goes on to speculate that the palisade

“was probably created to separate elite from hoi polloi, with the goal of emphasizing the priestly rulers’ separate, superior socially critical connection to the divine. At the same time the palisade was intended to welcome the citizenry — anyone could freely pass through its dozen or so wide gates. Constructed at enormous cost, this porous architectural folly consumed twenty thousand trees.” [33]

Here we have a classic case of a pseudoarchaeologist who “begins with a known quantity and stretches it into the unlikely to conclude the implausible.” Why would a fortification have been built so as to let “anyone … freely pass”? Mann is always ready to be impressed on behalf of his readers, who may otherwise be skeptical of his interpretations.

2. Were the mounds in Cahokia constructed by human beings?

In response to my rebuttal, Mann is emphatic that the earth mounds in Cahokia were man-made. He points out that over 500 peer-reviewed papers have shown this to be the case, and he “suspect[s] that one couldn’t find a single peer-reviewed journal article asserting [that they were natural formations] written in the last 80 years.”

What is not noted in this assertion, however, is how questioning the human influence on the mounds’ formation is discouraged. Fowler, for example, maintains that “those who proposed that Monks Mound was a natural phenomenon were probably influenced by racist attitudes,” [34] even though the skepticism was often linked to the level of technology present, not racial factors. Other attempts to suppress skepticism concern those interests that benefit from the aggrandizement of the Cahokian archaeological site.

One of these interests is tourism, and the excitement that can be generated by exaggerating the cultural accomplishments of prehistoric Cahokians. One of the original archaeologists who excavated the Cahokia site, Warren K. Moorehead, for example, used the idea that the mounds were man-made to promote the preservation of the area. According to Fowler, Moorehead “took the position that the mounds were all man-made and that even discussing the possibility of the mounds being natural formations would greatly injure attempts to make the area a state park.” [35] These political pressures mean that the consensus about the mounds’ formation should be treated with a certain amount of skepticism and the evidence provided must be evaluated rigorously.

There is evidence, however, pointing to the man-made character of some of the mounds (it is also possible that some were added on to preexisting natural formations). The most likely scenario is that these mounds were constructed for burials, since this occurred in many Neolithic cultures in Europe. It has been noted that the beaker culture that built the initial phase of Stonehenge, for example, “buried their dead singly, in graves containing a dagger, a bow and arrow, some ornaments, and a beaker. Over this grave they piled earth in a round mound.” [36] Many other sites show the historical existence of barrows “designed for the collective burial of the dead; they were between 100 and 400 feet long, between 30 and 50 feet wide, and about 12 feet high.” [37] One mound in Cahokia also contains several burials, which includes similar types of grave goods.

Cahokianists, however, have speculated about many additional functions besides burying the dead. The largest amount of “envisioning” has occurred in the case of Monks Mound and “downtown Cahokia” more generally. Monks Mound is characterized as a “pyramid” by Pauketat, [38] which involves the advocacy-driven stretching of definitions. [39] It is claimed that this mound had a large temple or building for the elite at the top, making it a kind of an earth ziggurat, similar to those found in Mesopotamia. [40]

It is not clear, however, how it has been determined that this temple existed. Fowler notes that, at the top of the mound, there was “evidence of intense construction activity, which included large buildings, fences, posts, and a small platform mound.” [41] But he also points out that “glass beads, a cast copper bell, and other historic material, along with the remains of an unusual building that had not been constructed in the usual wall-trench method of Missisissipian Indians” was found. [42] The latter findings would indicate that the remains were probably post-contact, as Cahokians did not appear to have the technology to cast metals or make glass (Monks Mound was used by European settlers after contact).

Dubious speculation also appears to have intruded into the analysis of the formation of the mounds, especially Monks Mound. There are indications of this in the works of Woods, Fowler and Dalan et al., which maintain that Monks Mound was created, not just by continuously dumping basketfuls of earth, but “with an impressive display of engineering savvy” (the words of Mann) to prevent slumping. Woods argues that this was done by creating a clay base “900 feet long, 650 feet wide, and more than 20 feet tall,” even though, as Mann points out, “clay should never be selected as the bearing material for a big earthern monument” as it swells and “over time heaving will destroy whatever is built on top of it.” This was evidently counteracted, according to Woods, by maintaining the slab “at a constant moisture level: wet but not too wet.” To prevent the clay from drying, “Cahokians encapsulated the slab, sealing it off from the air by wrapping it in thin, alternating layers of sand and clay.” [43]

But is it likely that Cahokians had such knowledge of soil engineering to separate out various types of soils and recombine them in accordance with this understanding? The encapsulation of the “slabs” by layering would not have just come about incidentally. The level of engineering required would involve experimentation and research, both unlikely without writing. And if they had this understanding, why would they have chosen to build such a large unsuitable base? This is where a comparison with other mound building cultures would be instructive. Do they show evidence of the sophistication that is being claimed in the case of Cahokia?

3. What did the dwellings in Cahokia consist of?

In discussing Cahokian dwellings, Mann maintains that there were “hundreds of red-and-white plastered homes with high-peaked deeply thatched roofs like those on traditional Japanese farms.” He then extends this description in his response to my rebuttal by stating that they were waddle and daub homes like those that existed in 17th Century England. Hundreds of these dwellings, according to Mann, have been “uncovered” and “identified” in Cahokia using “modern [archaeological] techniques.”

Although I had erroneously assumed that Mann’s description was one of wood plank homes covered by plaster (stucco), thus explaining my misguided question about nails and saws, I do not see how I could have developed an alternate understanding by looking at 1491’s endnotes. Mann claims that the endnotes indicate “the source of that particular description” (Envisioning Cahokia, pp. 64-78), but this source is only used with respect to determining a “Cahokia chronology“ (inferred from radiocarbon dating), not dwellings, and only page 69 is referenced. [44]

It is also important to point out that it is not correct to claim that wattle and daub houses were “uncovered.” The “identification” of these dwellings was inferred from impressions in the earth. The notion that “plaster” was used has not been demonstrated. [45] Nor is it possible to determine the nature of the roofs — whether they were hipped, peaked, gabled, etc. — from impressions of what are assumed to be roof supports and wall-trenches. Is Mann’s “evidence” from artist’s reconstructions? It is also not clear what Mann is talking about with respect to the “lengthy description of research on Mississippian pigments and house colors, including those at Cahokia” in J.R. Swanton’s The Indians of the Southeastern United States. This discussion is certainly not obvious, since Swanton’s discussion of Indian dwellings pertains to the post-contact period.

Mann’s comparisons with Japan and England are also inappropriate and misleading as these were Iron Age cultures. A valid parallel would be the homes of Neolithic peoples in England or the Orkney Islands (Skara Brae). In the case of the former, they “lived in tents or pits sunk into the ground and covered by wattle.” [46] Recently, indications of eight houses were discovered and thought to be associated with the cultures that made the third phase of Stonehenge — a Bronze Age culture. It has been noted that “each house, made from sticks woven together and crushed chalk, was no bigger than 14 to 16 feet square and had a hard clay floor and a central fireplace. Indentations in the floor were interpreted as post holes and slots that once anchored wooden furniture.” [47]

Also interesting is how early European housing is discussed compared to the exaggerated celebratory language that is used in Mann et al.’s writings about Cahokian dwellings. Houses in Ango-Saxon villages in England (450-1066 AD), for example, are explained as follows:

“the material conditions of peasant life were primitive and precarious. Excavations … show that the peasant and his family lived in a rude timber hut of only one room, about 10 feet by 18, with an open hearth … The villagers had few material goods — excavations have turned up only some iron knives, iron combs, bone pins, cattle bells, and loom weights. Not possessing the potter’s wheel until the seventh century, the early English made coarse and unshapely pottery.” [48]

The materials discovered in Cahokian sites indicate a lower level of technology (there were no looms, draught animals, or iron tools), but they are characterized by Mann’s sources as “elaborate” and “spectacular.”

4. Was Cahokia a “busy port”?

To substantiate this claim, Mann uses the pseudoarchaeologist’s appeal to authority and provides a quotation from Fowler’s The Cahokia Atlas. When one looks at the page cited, however, no evidence is provided by Fowler to support this assertion (it appears to be a “large claim” shaped by wishful thinking). Presumably, this conclusion is drawn from the fact that materials from other geographical areas were discovered in Cahokia, as occurred in the case of materials from the Andes appearing at the mouth of the Amazon (this case is referred to by Mann in his response to my rebuttal). From this it is inferred that a great deal of “trade” must have been taking place, and trips made by large numbers of boats were required to sustain this complex economic activity.

But materials can diffuse across large distances just through the interactions of various groups over time. The fact that materials from hundreds of miles away are found in archaeological sites does not mean that they were traded; they might not even have been intentionally transported. After contact, for example, explorers came across aboriginal groups who possessed European materials, even though they had not yet encountered the newcomers face to face.

This raises questions about how archaeologists determine if a site was an ancient “busy port”. According to the dictionary definition, “a port is a harbour, plus terminal facilities: piers, wharves, docks, store buildings, and an infrastructure of roads and rivers or canals.” To what extent have these indicators been discovered in Cahokia? One would expect there to be some evidence of boats, wharves, storage facilities, roads, etc. in the excavations. In the case of Mann’s example of London, for example, archaeological evidence of the port dates back to the Roman period. A document was found in the 10th Century that “records tolls chargeable at Billingsgate, in respect of vessels from Normandy, France, Liége, etc., and those of the Easterlings.” Records also show that activity at the port increased after the Norman Conquest (1066), when “there was a further influx of foreign merchants into London from Normandy, Flanders, Italy, Spain and other European countries who found London ‘fitted for their trading and better stored with merchandise in which they were wont to traffic.’” [49]

Although the above focuses on just one aspect of Mann’s book, his analysis of Cahokia is not even the worst example of his politically-inspired research agenda. A more problematic area concerns his analysis of the “Great Law of Peace”, where the existence of Deganawidah, “the Peacemaker,” is recounted as historical fact after noting that some archaeologists maintain that he “belongs entirely to the realm of legend.” [50] The Baron de Lahontan is also assumed to be a legitimate source (when he is widely recognized as a “travel liar” who invented events and conversations with a mythical Huron chief he called “Adario”). [51] And then there is his highly dubious use of Benjamin Franklin’s quote about “ignorant savages” to justify the view that that the founding fathers were influenced by the Iroquois confederacy in their development of the American constitution. [52]

Conclusion: The political pressure to sew a shirt on a button

Although I hope that my initial analysis of part of Mann’s book will lead Native Studies scholars to rethink their uncritical use of this source, it is doubtful that this will happen. This is because Mann’s thesis about the great size and “sophistication” of pre-contact aboriginal societies is consistent with the anti-evolutionary sentiment in current works on aboriginal-non-aboriginal relations. The mistaken assumption that culture is tied to race, and therefore we should feel ethnic pride about the cultural accomplishments of our ancestors, is preventing an impartial examination of historical processes. The pernicious and condescending postmodern idea that historical interpretations should be devoted to raising the self-esteem of oppressed groups is an obstacle to the acquisition of knowledge about humanity’s development.

This brings me to the main point of contention that many have with Disrobing the Aboriginal Industry – that it accepts the idea that cultures evolve. Sinclair maintains that the theory is “outdated”, but he does not show how this is the case. In fact, he relies on the pseudoarchaeology of Charles C. Mann as evidence, which de-links technological complexity from social complexity. Besides, ideas do not “date.” They are either proven to be wrong by more recent evidence, or remain relevant. Their age has nothing to do with it.

Scientific archaeology assumes that technological development is the major explanatory factor in the development of humanity. This is why cultures are classified according to the Stone, Bronze and Iron Ages. An archaeology textbook even provides the following as two “major developments” in human prehistory: the origins of 1) complex foraging societies and food producers and 2) urban and literate state-organized societies. [53] A denial of cultural evolution would label the recognition of these two developments as “outdated.”

Cultural evolution is just as legitimate a theory as biological evolution. But while the battle over biological evolution largely has been won (except in venues such as Native Studies programs!), cultural evolution still faces opposition. This is because cultural evolution helps us to understand political relations and possibilities for social cooperation. Those who want to mystify future possibilities for human progress have much to lose from the greater understanding of the human condition that the theory of cultural evolution offers.

FOOTNOTES

1. Charles C. Mann, 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus (NY: Vintage Books, 2006), p. 250

2. Mann, p. 379.

3. Mann, pp. 134-5.

4. Mann, pp. 63-4; 137. Mann maintains that “indigenous peoples in New England were not technologically inferior to the British” at the time of contact and compares Mexica (often called Aztec) philosophy to “the Vienna Circle and the French philosophes and the Taisho-period Kyoto School.” He supports his idea about the technological advancement in New England with arguments that guns were less effective than Indian bows and arrows, moccasins “were more comfortable and waterproof” than European boots, and “birchbark canoes were faster and more maneuverable than any small European boat.” But the societies that the British colonists had evolved out of already had developed all this technology (i.e., bows and arrows, canoes, slippers, etc.) thousands of years earlier. Why would they have replaced bows and arrows with guns or developed sailing ships if there was no survival advantage for doing so? And while the British had the technology to make bows and arrows and canoes if they so wished, Indians did not have the know-how to manufacture a gun or a sailing ship.

5. Mann, p 42. He maintains, for example, that pre-contact Indians in New England were “like affluent snowbirds alternating between Manhattan and Miami.”

6. Mann, p. 390.

7. The opposition to calling societies uncivilized, in fact, is noted by Mann. Mann, p. 390.

8. Mann, p. 390.

9. Mann, p. 335.

10. Mann, p. 291.

11. Felix Barker and Peter Jackson, London: 2000 Years of a City and Its People (New York: MacMillan Publishing Company, 1974), p. 20.

12. For particularly speculative “artist’s reconstructions” see Rinita A. Dalan, et al., Envisioning Cahokia: A Landscape Perspective (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2003), pp.72-76. In these reconstructions, not only are the villages drawn, whole scenes of village life are imagined.

13. Clayton Roberts et al., A History of England, Volume I (New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2002), pp. 93-98.

14. Barker and Jackson, pp. 15-22; and Roberts et al., pp. 77-113.

15. Roberts et al., p. 126

16. Roberts et al., pp. 8-9.

17. Garrett G. Fagan, “Diagnosing pseudoarchaeology,” in Garrett G. Fagan (ed.), Archaeological Fantasies (New York: Routledge, 2006), p. 43.

18. Fagan, p. 29.

19. Fagan, pp. 29-37.

20. Fagan, pp. 41, 43.

21. N.C. Flemming, “The attraction of non-rational archaeological hypotheses,” in Fagan (ed), Archaeological Fantasies, p. 61.

22. Flemming, p. 52.

23. Mann, pp. 291-2.

24. Mann, p. 392.

25. Scarre and Fagan, Ancient Civilizations, 3rd Edition (New Jersey: Pearson, 2008), p. 7.

26. Mann, p. 293.

27. Pauketat, pp. 4, 127.

28. Fowler, p. 201.

29. Pauketat, The Ascent of Chiefs (London: University of Alabama Press, 1994), pp.86- 87, 180.

30. Mann, pp. 291-2.

31. Fowler, Cahokia: The Great North American Metropolis, p. 119. Fowler notes that “they had not dug very far before they came upon the characteristic dark stains in the yellow soil indicating archaeological features. The features were a series of trenches that had once held the logs of a great wall or palisade. As they dug further, they found evidence of not one but four palisades.”

32. Fowler, The Cahokia Atlas, pp. 189-90.

33. Mann, p. 299.

34. Fowler, The Cahokia Atlas, p. 98.

35. Fowler, The Cahokia Atlas, p. 23.

36. Roberts et al., p. 10.

37. Roberts et al., p. 7.

38. Pauketat, Cahokia, pp. 2, 127.

39. For a discussion of the inappropriate use of the term “pyramid,” see Fagan, Archaeological Fantasies, p. 37.

40. See Brian M. Fagan, Ancient Lives, Figure 3,13, p. 73 and Figure 12.9, pp. 326-7 for a “reconstruction” of ziggurat in Eridu, Iraq. As these are drawings, a further investigation is required as to whether these drawings are speculative or a realistic representation of the archaeological site.

41. Fowler, Cahokia, p. 159.

42. Fowler, Cahokia, p. 161.

43. Mann, pp. 292-294.

44. Mann, p. 452.

45. In fact, Pauketat provides a diagram of a pole-and-thatch building, where the walls are covered by thatch and earth is heaped up against the walls. The description of this dwelling does not mention “plaster”, which is assumed in this context to mean smeared mud not actual plaster (a material made of lime, sand and water, or in the case of the ancient Greeks and Romans, gypsum, marble dust and glue).

46. Roberts et al., p. 9.

47. John Noble Wilford, “Village May Have Housed Builders of Stonehenge”, The New York Times, Jan. 31, 2007 (accessed August 2010).

48. Roberts et al., p. 55.

49. Port of London Authority website (accessed August 2010).

50. Mann, p. 370.

51. Mann, p. 376.

52. Mann, p. 374. On page 382 Mann responds to criticisms about using this quote, maintaining that rejecting it as evidence would be tantamount to saying that aboriginal groups had no influence over European society.

53. Fagan, Ancient Lives, p. 15.

[ Second button image via icons.mysitemyway.com ; needle and thread via berninahamilton.co.nz ; aerial photo of Monks Mound via Running ‘Cause I Can’t Fly ]

→ ←

Return to

Table of Contents

→ ←

At this point in things, a new voice entered the fray: University of Manitoba sociology professor Dr. Christopher Powell. His first contribution took the form of this comment.

Sept. 2, 2010:

Comment on “Sewing a Shirt on a Button”

As a social scientist, I think Widdowson is on shaky ground when she accuses others of pseudoscience. The version of evolutionary theory that she argues for is one informed by the “social Darwinism” associated with figures like Herbert Spencer, who in the nineteenth century altered Darwin’s ideas on evolution to suit the priorities of a classist, sexist, and racist approach to social issues and to the comparison of differing human societies.