One little planet. One BIG farm.

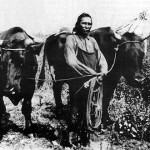

Since the ’30s, the days of the family farm have been numbered. The dustbowl sucked young farmers off the land faster than you can say “plague of grasshoppers.” But there were always dirt die-hards who hung on — even flourished — once the rain fell again and the insecticide giants and genetically modified crop scientists bent their heads to the task.

Since the ’30s, the days of the family farm have been numbered. The dustbowl sucked young farmers off the land faster than you can say “plague of grasshoppers.” But there were always dirt die-hards who hung on — even flourished — once the rain fell again and the insecticide giants and genetically modified crop scientists bent their heads to the task.

So there still are family farmers. Still those glorious fields of gold you drive past down rural roads, the wind buffeting the hand you trail out the window, the radio booming out Northern Cree Singers tunes. Yet the dominant trend toward corporate farms — big business owners operating on a mass scale, ploughing and seeding tracts of land not for the benefit of rural economies, but for shareholders in urban boardrooms — has never halted. Those entities dug in and wheeled and dealed and cultivated hectare after hectare until all the eye could see on some of those country drives was the outdoor factory floor of industrial farming.

So there still are family farmers. Still those glorious fields of gold you drive past down rural roads, the wind buffeting the hand you trail out the window, the radio booming out Northern Cree Singers tunes. Yet the dominant trend toward corporate farms — big business owners operating on a mass scale, ploughing and seeding tracts of land not for the benefit of rural economies, but for shareholders in urban boardrooms — has never halted. Those entities dug in and wheeled and dealed and cultivated hectare after hectare until all the eye could see on some of those country drives was the outdoor factory floor of industrial farming.

In the United States, corporatisation of the land met with more resistance. Nine midwestern states have, over time, adopted restrictions by statute or constitutional mandate. Corporate farming has been viewed with suspicion in some regions.

But here in Canada, one corporation called One Earth Farms is sowing its oats and barley and wheat and whatnot all over Alberta and Saskatchewan and Manitoba, for the financial betterment of its majority owners in Toronto and, it turns out, some of its First Nations partners too.

The land comes from First Nations. The venture comes from Bay Street. It started with the friendship of a man in a suit — Eric Sprott — and former Assembly of First Nations National Chief Phil Fontaine. Sprott brought in another businessman, Kevin Bambrough, who Fontaine in turn introduced to Blaine Favel, former leader of the Federation of Saskatchewan Indians. And from there, One Earth became a partnership in which Fontaine and Favel are directors under CEO Larry Rudd, who is also currently a director of Viterra, the largest grain company in Canada.

One Earth is 58% owned by Sprott Resources Corporation, making it more business than farmer’s tan. Such is the nature of cropping and ranching in the corporate world:

“Sprott Resource Corp. invests and operates through its subsidiaries in the natural resource sector. We currently have investments and operations in oil and gas, agriculture and agricultural nutrients as well as a large position in physical gold bullion. … We are dedicated to generating consistently superior returns on capital for our shareholders … by acquiring or starting attractive businesses at the right time, growing the value organically or through accretive acquisitions and by maintaining financial flexibility to be responsive to the needs of our businesses and to capitalize on new opportunities.”

It’s interesting to note that one of the big investors in One Earth Farms Corporation is an entity called the CAPE fund. It’s a $50 million private-sector investment fund founded by the family of former Prime Minister Paul Martin — and 21 of Canada’s leading companies.

It’s interesting to note that one of the big investors in One Earth Farms Corporation is an entity called the CAPE fund. It’s a $50 million private-sector investment fund founded by the family of former Prime Minister Paul Martin — and 21 of Canada’s leading companies.

CAPE Fund says its mission is to “further a culture of economic independence, ownership, entrepreneurship and enterprise management among Aboriginal peoples, on or off reserve, through the creation and growth of successful businesses.”

So, in theory, all this cheery portfolio talk should translate to more First Nations in charge of their own farms and farm profits, even with Sprott Resources holding a 58% controlling ownership in One Earth. And that’s a good thing, right?

Very troubling but no big surprise that ,’ its all about the money Fontaine’ was involved. The Indian Act has “taught” him well

I do note with interest that it will be a “sustainable” agro-business, assuming that’s not oxymoronic.